As I mentioned previously, I'll be contributing food-related features and restaurant reviews to ThaiDay, the paper bundled with the International Herald Tribune. I'm going to be posting those articles here, and I'll begin with a feature/restaurant review that ran on page 5 of today's ThaiDay (Thursday is food day at ThaiDay!). I'd like to thank Features Editor, Nick Grossman, for letting me do this. (And for those of you who may have already seen the print version, the version below is the original, and will vary slightly from the editor's take, but I will include the same pics as in the article.)

Vive le Soi! (ThaiDay, 02/03/06)

Live the vie en rose in Bangkok's French Quarter.

For authentic regional food, Bangkok’s ethnic enclaves are an obvious destination. What better place to go for hummus and tabouli than the Nana area? Thinking of dhal and chapatti? Think of Phahurat, Bangkok’s Little India. And Yaowarat, Bangkok’s Chinatown, is the obvious choice for all foods Chinese. These neighborhoods and their cuisines are well established, however in recent years a new ethnic district has begun to emerge in Bangkok. Home to a bakery, an ambitious butcher shop, a restaurant popular among French expats, a wine shop, and numerous cafés, Soi Convent, “Bangkok’s Champs Elysées”, has all the attributes of a Parisian arrondisement. The following is a rundown of the French food establishments found in Bangkok’s newest ethnic enclave.

La Boulange

2-2/1 Convent Road

02 631 0355

For many, the first image that comes to mind when most people think of French food is bread, and it is thus fitting that the first French business to become established on Soi Convent was a bakery. La Boulange was started up seven years ago, and was probably Bangkok’s first high-quality independent bakery. In the beginning the small café/bakery sold a small selection of high-quality pastries and sourdough breads baked on the premises in an imposing wood-burning oven. However, other than a cup of coffee or a simple sandwich, La Boulange was largely a take-home affair, and never progressed past this.

Tempting pastries at La Boulange.

After less than a year in business, La Boulange was taken over by Bangkok-based French hotelier, Robert Molinary. The wood-burning oven was removed, and under the guidance of an experienced French chef, a greater emphasis was put on bistro-type meals and wines. “This business is more competitive now,” explains acting GM and self-proclaimed “food engineer” Patrick Parthonnaud, about the decision to revamp the restaurant. Today, La Boulange’s breads are baked in factories in Bangkok and Pattaya, however, for those concerned, Parthonnaud assures me that “The bread is still exactly the same.” There are now as many as 20 varieties of pain sold at La Boulange, including the hearty country-style loaf, pain de campagne, a sourdough-rye bread, and such Parisian staples as baguette and batard. The bakery is still producing pastries, and La Boulange’s marble-topped street front tables are probably the most pleasant place in Bangkok to take a café au lait.

Gargantua

10/2 Soi 6 Convent Road

02 630 4577

Tucked into the end of an unremarkable side street, Gargantua is the unusual name behind a recently opened French-style butcher shop. Part owner, Arnaud Carré, is a fifth-generation butcher from Brittany who has been involved with meat since childhood. “I used to work in my

Gargantua, a French butcher's shop on Soi Convent, offers hard-to-find cuts of meat and exotic sausages.

father’s butcher shop as a child,” explains Carré between endless cigarettes and coffee. After running his father’s business for several years, Carré spent 10 years in the US working for a chain of steakhouses, and eventually opened a French-style boucherie in Manhattan. When asked why he decided to relocate to Bangkok, he replies confidently, “I am a man of challenge.”

Challenges aside, Gargantua is one of the few domestic producers of elusive French products such as terrine de lapin, rabbit terrine; merguez, Algerian-style spicy lamb sausages; and saucisse aux herbes, fresh herb sausages; as well as choice cuts of beef and veal. All of the meat products, except for lamb, are Thai, and when asked about the quality of Thai beef, Carré is quick to reply, “The quality of meat here is fantastic. High quality Thai beef is close to

American beef, if prepared right.” After less than a year in business, Carré already has plans to open another branch of Gargantua “somewhere in Bangkok”, and will soon be expanding his range of merchandise to include a greater variety of fresh sausages and other products.

Wine Connection

Unit 5 Ground Floor, Sivadon Building

1 Convent Road

02 234 0388

www.wineconnection.co.th

You’ve bought yourself a baguette and a few slices of pâté, now what do you drink? The obvious choice would be wine, and since 2002, Wine Connection on Soi Convent has proven itself to be one of the best places in the city to buy a bottle. Wine Connection’s CEO and founder, Michael Trocherie, hails from the south of France and previously worked in Vietnam

exporting French wine to other parts of Asia. After seven years of this, he decided to move to Bangkok and import instead. “I wanted to be on the other side of the business,” explains Trocherie. Wine Connection began as an online business, and opened its first shop on Sukhumvit 32 in 2000. Since then the store has expanded to various locations in Bangkok and Thailand, as well as Singapore.

The search for that perfect bottle is not difficult at Wine Connection.

Part of the reason for Wine Connection’s success is its shops; they are attractively designed and well organized, just like a good wine shop in Europe or the US. And there is also volume; the Soi Convent branch of Wine Connection alone sells more than 250 kinds of wine, with a large proportion of these being, not surprisingly, French. Thankfully for the consumer, Wine Connection emphasizes mid-range wines, and several excellent bottles can be found for 600 baht or less. I ask Michael for a recommendation and he suggests a Domaine de la Begou, a red from southern France. “It won a gold medal in France, but it’s not a famous name,” he explains. “It’s a very good wine, but not expensive, exactly the kind of thing we like to sell.”

Cafés

Any self-respecting French street wouldn’t be caught dead without its cafés, and Soi Convent is no exception. Starting at the Silom end of Soi Convent is a branch of the ubiquitous Starbucks (1/3 Convent Road), equipped with Wi-Fi for those who prefer to read Le Monde online with their coffee. On the same side of the street is the Café Swiss (3 Convent Road, www.swisslodge.com). More a restaurant than a café, the location offers a pleasant outdoor dining area and a European-style breakfast buffet. The Tung Who Coffee Shop (13/1 Convent) across the street serves “Original Thai Coffee” and a number of Chinese/Thai dishes. Goûte House is a small bakery (French only in name) selling a variety of pastries including palmiers, a sweet of French origin. And finally, near Sathorn, are the Café de Convent, a small café-cum-florist, and Goodwill, an attractive café with a Thai menu

(Boxed restaurant review)

Indigo

6 Convent Road

02 235 3268

indigobangkok@yahoo.com

Located in an attractive former schoolhouse and boasting one of the loveliest outdoor dining areas in town, Indigo has been a popular meeting place for French expats since opening five years ago. I had never visited the restaurant until a friend of mine, a French cookbook author, urged me to go, expressing repeatedly that it was “very French”. I wasn’t sure what she meant by this, and not once did she mention the restaurant’s food, but I trust her judgment and decided to drop by.

Arriving at 4:45 to an empty restaurant and a confused waitress, my companion and I were seated and promptly given lunch menus. We requested the dinner menu, and I began with one of the specials, rocket salad (190 baht) and my companion with warm goat cheese salad (320 baht). The rocket salad reminded me of rocket salads I’ve made at home (which is a good thing,

but not particularly exciting when eating out), but the warm goat cheese salad was more interesting; a bed of mixed greens supporting two toasts topped with fresh thyme and melted rounds of local goat cheese. My salad was followed by blanquette de veau à l’ancienne (390), a notoriously difficult to make “stew” of veal. I should by know not to order any dish employing the word “traditional”, and the blanquette was flat, the cream and egg yolk-based sauce heavy and lacking the zest and spice that more current interpretations of the dish often allow. And as if to rub my nose in my lackluster choice, my companion purred over her bar à la provençale (390 baht), fillets of sea bass pan-fried with olives capers, tomatoes, lemon and basil. We’ve all seen this dish (and this fish) before, but again, she had made the wiser selection, and the result was satisfyingly crispy, savory and tart. Our food was taken with the house white wine (120 baht), a predictable Chardonnay, and we ended our meal by sharing a tarte fine aux pommes et glace vanille (170 baht), a freshly-baked apple tart with vanilla ice cream. Tasty, but I always get a little sad when the warm tart melts all of my ice cream.

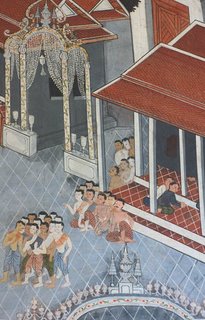

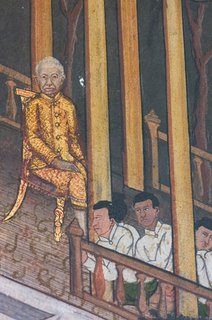

The old world charm of Indigo's whitewashed interior.

Up to this point our food had been underwhelming and overpriced, and the setting perfect, and I was wondering if this was what my friend meant by “very French”. However, my understanding came later, when the owner of Indigo, initially wary of my picture snapping and wandering around his restaurant, caught on that I was a food critic, invited himself to sit down at our table and began to gush about his restaurant, bringing us wheels of French cheese and frightfully large loaves of bread to look at. Cynics would say he was doing this to promote his restaurant, and they would undoubtedly be correct, but I found this unabashed love of food touching and very French. If only this affection would carry over to the restaurant’s kitchen.