Guardians of art (ThaiDay, 11/03/06)

Veeraphong Suwannasin is clearly a man excited about his work. As I wander around Phra Thi Nang Song Phanuat, a graceful century-old structure on the grounds of Wat Benchamabophit, he is more than happy to describe the stories depicted in the structure’s vast murals, and is

eager to provide information about the building. However, Suwannasin’s job, and the structure we are in are anything but typical. Suwannasin is a member of the Department of Fine Arts’ mural restoration team, and Phra Thi Nang Song Phanuat is the former ordination hall of King Chulalongkorn, Rama V.

Established 30 years ago, the Department of Fine Arts’ mural restoration team has been responsible for the restoration, upkeep and renovation of an estimated 1,000 sites in Thailand. These restorations can range in subject from Buddha statues to stucco wall designs, but the team is particularly experienced at restoring and protecting the painted murals that often line the inside walls of Buddhist temples in Thailand. They are the only team of its kind in the

country, and are thus responsible for the restoration and upkeep of some of the most important Buddhist art in Thailand. The team’s current restoration efforts at Phra Thi Nang Song Phanuat involves murals, and is, in the words of Suwannasin, a particularly “special” job. “It will take us longer than usual, and many influential people expect to see good work,” he explains.

Phra Thi Nang Song Phanuat is one of four structures that were originally located in the Grand Palace as part of the Temple of the Emerald Buddha. The buildings served as the ordination hall of Prince Chulalongkorn during his time as a monk, and when he later became king, he

ordered the structures to be relocated to the grounds of his newly commissioned temple, Wat Benjamabophit. After being moved, they were joined together and served as the residence of the temple’s first abbot. Not much later, a series of 20 murals depicting the life and reign of King Rama V were painted on the inside walls of one of the structures.

As with most murals in Thailand, the murals at Phra Thi Nang Song Phanuat have suffered a great deal of wear and tear over the years. This includes water damage that erased an entire wall of paintings, and cracks that were the result of previous structural repairs. Large chunks

of the murals have come loose, and a number of hollow spots in the plaster have formed. The structure was previously renovated by the team in 1985, but ongoing water damage at the base of the paintings, a common problem with temple murals, necessitated a new renovation.

Despite the difficulties involved and the high profile of the structure, this type of job is nothing new to the team, explains Somsak Taengphan, administrative head of the group. “We have to train our workers and teach them the rules [of restoration],” explains Taengphan. “All members of the team have art backgrounds, but painting and restoration are not the same.”

The team has 14 permanent members, but also employs the help of other artists for particularly big jobs. Taengphan explains how restoration work on Wat Suthat, a well-known Ratanakosin-era temple in Bangkok, required the help of more than100 artists, and took more than three years.

The ongoing work at Phra Thi Nang Song Phanuat involves six full-time workers, and while there, I am given a crash course in mural restoration by Taengphan and other members of the team. They explain that the first step in restoring murals involves removing the surface dust and grime that has accumulated over the years. This is typically done by applying a sheet of mulberry paper to the surface of paintings and painting over this with a wet brush. “The paper absorbs the dirt and can be removed without damaging the murals,” explains Suwannasin. The

use of mulberry paper may seem like a quaint throwback, but according to Virachai Suksawadi, a veteran member of the team, “The most important thing is to use the original materials.” Despite the advances of modern technology, the team strives to use the original methods and materials whenever possible. This leads them to employing such obscure products as buffalo skin, sugarcane juice and tamarind seeds, typically gathering and preparing these materials themselves.

After removing dust and grime, the second step involves securing the plaster base that supports the murals. Over the years, cracks have developed, pockets of air have formed, and water has caused the plaster to separate from the foundation. Virasuksawadi demonstrates how pockets of air are found simply by knocking on the plaster and listening for a hollow

sound, and describes how holes and cracks are filled with epoxy using a large syringe. After injecting the epoxy, loose pieces of plaster are then gently pushed back against the foundation using a cloth-coated pad held over a layer of mulberry paper. For larger structural cracks, occasionally holes are drilled to the foundation, which are then filled with a mixture of glue, plaster and fine sand.

The final step involves painting. This normally involves touching up faded drawings rather than repainting missing or damaged art, which is, for the most part, frowned upon. “We want to make our work look as authentic as possible, but if we have to repaint something, then we have to make it clear that that our work isn’t the original,” explains Virasuksawadi. This is done by discretely outlining or bordering the areas that have been restored or redrawn.

In certain situations where large portions of work are missing, repainting can be an option. “It depends on the work,” replies Virasuksawadi. “If too much is missing, we don’t know what used to be there and we can’t paint.” In the case of Phra Thi Nang Song Phanuat the team was asked by Wat Benjamabophit to repaint an entire section of murals that was previously destroyed by water. There were no photographs of the paintings that used to exist, and the team was left to rely on no more than a few written descriptions, the stylistic precedence of

remaining paintings and other similar murals as a model. “Normally this is not done,” explains Suwanasin, “But this is a special job, lots of important people will see it, and the temple asked us to do it.” For large areas that need to be repainted, a base made partially from a gum that comes from tamarind seeds is applied to the wall. Then the drawings are then outlined in pencil and painted in using tempera, as opposed to modern watercolors.

The work on Phra Thi Nang Song Phanuat, which began in late November is expected to continue until May, and is, in the words of Taengphan, “a perfect job”. “It’s a good size, it’s fun work, and our results will be here a long time.” Without the efforts of Somsak Taengphan and his team, it is almost certain that the murals at Phra Thi Nang Song Phanuat, as well as other precious elements of Thailand’s artistic heritage, would undoubtedly fall into obscurity.

Halls of History (Boxed text)

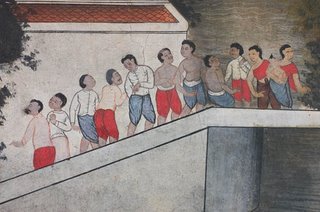

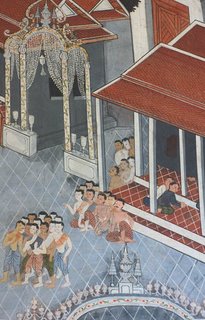

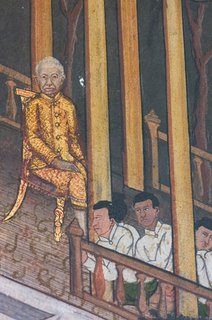

The murals of Phra Thi Nang Song Phanut are unusual in that, rather than illustrate the various life stories of the Buddha as with most temple paintings, they depict events during the life of King Rama V. Painted by unknown artists during the reign of King Rama V, the 20 panels depict the life of the King in chronological order, beginning with his top knot cutting

ceremony at the age of 13, and continuing with his ordination, coronation, and travels within Thailand and to foreign countries. One panel in particular describes the story of a man-eating crocodile in Chachoengsao that King Chulalongkorn was involved in exterminating. Yet another panel even depicts the relocation of Phra Thi Nang Song Phanuat from the Grand Palace to its current location at Wat Benjamabophit. The murals are valued for their accurate

depictions of real people, including depictions of King Rama V’s father, King Mongkut, Rama IV, and for the insight they provide into various aspects of royal life in Ratanakosin during the reigns of Rama IV and Rama V, including King Rama IV’s interest in astronomy, and details of his funeral ceremony.