This week's Cornucopia is about ahaan kin len, Thai snack food, and is, as always, an interesting read. In it Mr Sukphisit mentions several dishes that I've heard of, but haven't had the chance to sample, and he does a great job of tying in culture, langage and food.

Sukhumvit Soi 38

This is a street in Bangkok that is particularly known for its street food. Every night at about 7:00 vendors push their carts out to the intersection with Sukhumvit and the hungry follow them there. The area has been well known for ages, but I get the feeling that it might be in the process of becoming a Tourist Attraction, as there were quite a few lost-looking foreigners clutching guidebooks, and the prices on some dishes were substantially higher than usual. I must admit that I've only recently discovered this area; I live on virtually the opposite end of Bangkok and don't tend to eat Thai food outside of my area too often. However, I'm looking into moving--possibly to this street--and the added benefit of good street food might make it an easy decision!

Here's a view of the street from the Thong Lor BTS station:

This guy is selling khao man kai, Hainanese chicken rice:

The guy on the right is making khaa muu, pork leg stewed in spices:

And to his left is the noodle stand I ate at. I had yen taa fo, a Chinese noodle dish. Here it is being prepared:

He's adding phak bung, a crunchy green vegetable known in English as morning glory. The noodles were excellent--probably one of the best bowls of yen taa fo I've had--but at 50 baht, also one of the most expensive! However I'm always willing to pay a bit more for good food, and ahem, atmosphere (the noodles were consumed while sitting on a plastic stool on the side of the road with me virtually dripping with sweat).

Luso-Siamese synergy

ThaiDay, 27/04/06

Tracing the roots of Portugal's influence on Thai cuisine.

I have some news for you: the green curry you ate last night is really a Portuguese dish. And your favorite som tam? Portuguese as well. Fancy a glass of cha dam yen, Thai-style iced tea? You have Vasco da Gama to thank for that. Well, OK, I’m exaggerating a bit, but it is essentially true that none of the above Thai dishes would have been possible without the help of the Portuguese.

This is because many of the ingredients and dishes that we consider Thai are actually fairly recent culinary introductions, a result of the influence of Portuguese traders and missionaries who visited Thailand starting in the 16th century. This 500-year-old exchange of produce and ideas had a profound impact on Thai food, and largely contributed to defining the cuisine we are familiar with today.

The area surrounding the Santa Cruz Church was once home to a community of Portuguese settlers.

The Portuguese were the first Europeans to visit Thailand, having arrived at the former royal capital of Ayuthaya in 1511. Establishing friendly relations with the court of King Ramathibodi II, the Portuguese were quick to take the exciting new products coming from the Americas and market them in Thailand. Thus saw the introduction of such modern-day Thai staples as tomatoes, potatoes, corn, lettuce, cabbage, chilies, papaya, custard apples, guava, pineapples, pumpkins, sweet potatoes, cashews, peanuts, and tobacco. Today these ingredients have been integrated to such an extent that their origin is largely forgotten, and few Thais are aware that their beloved chilies, for example, are actually a non-native species.

The Portuguese were also responsible for bringing products from other parts of Asia to Thailand, such as cinnamon from Sri Lanka and nutmeg and cloves from Indonesia. Perhaps the most significant example of this inter-Asian commerce was the trade of a simple leaf known in an obscure southern Chinese dialect as te: tea. The Portuguese brought tea from China and introduced it to Thailand and much of the rest of Asia, and were also largely responsible for popularizing the drink in Europe.

A great deal of the produce that Thais use on a daily basis are actually fairly recent introductions courtesy of Portuguese traders.

Other than introducing a new variety of raw ingredients, the Portuguese also had an impact on the way Thais cooked. This influence is most clearly seen in the area of khanom, sweets. In fact, Thai history claims that much of the Portuguese influence on Thai sweets can be traced back to a single person: Marie Guimar, the mixed-race Portuguese wife of Constantine Phaulkon, Greek explorer and high-ranking minister of King Narai. Guimar had a strong influence on the kitchen of the royal household, and by introducing the concept of baking and the use of ingredients such as egg yolks and flour—methods and elements unknown in Thailand but integral to Portuguese dessert making—she had an impact on Thai desserts that can still be seen today.

One of the most obvious examples of the Portuguese influence on Thai sweets can be seen in the numerous desserts that share the Thai word for gold, thong, a reference to the yellow/orange color imparted by the liberal use of egg yolks. These desserts include thong ek, thong yawt, thong yip, and foy thong, and are all variants of a family of Portuguese desserts known as ovos moles. Despite the passing of a half-century since their introduction, many of these sweets are still similar in form to desserts that can be found in Portugal to this day. To learn more about the production and origin of these desserts, I paid a visit to the factory of Kanomthai Kao Peenong, the largest producer of Thai sweets in the country.

I am given a tour of the factory byArin Pipattawatchai, Kao Peenong’s head of quality control, and an expert in the production of Thai sweets. She explains that all of Kao Peenong sweets are made by hand, still employing the same methods that were introduced by the Portuguese nearly 500 years ago. In the case of the Portuguese-influenced thong sweets, this process typically involves immersing duck-egg yolk combined with various other ingredients in simmering syrup. “For Thai people in the past, eggs were dinner food—they weren’t used for sweets,” explains Pipattawatchai. “This concept was introduced by the Portuguese.” We watch the production of thong yawt, made by dropping a thick paste of duck eggs, coconut milk and jasmine-scented flour into boiling syrup, resulting in firm, bright yellow balls that are both sweet and fragrant. The process for thong yip is similar, however the still-warm golden disks are pressed into small ceramic bowls to obtain their flower-like shape. The most interesting process of all is that of foy thong, whereby egg yolks are streamed into simmering syrup through a fine sieve, resulting in delicate, golden ‘noodles’ of egg yolk.

Making thong yip at Kanomthai Kao Peenong.

Another example of the Portuguese influence on Thai sweets can be found alongside the Chao Phraya River in Thonburi, in the neighborhood surrounding the Santa Cruz Church. This area was allocated to Portuguese and French traders when the capital of Thailand was moved from Ayutthaya to Thonburi, and is today known for khanom farang kutii jiin, a cake of Portuguese origin. The cake, a simple mixture of duck eggs, sugar and flour, is prepared by an improvised method of baking, which employs a bottom layer of heated gravel and a top layer of hot coals to simulate the effect of an oven, a kitchen tool not found in Thailand during the Ayuthaya era.

Along with food, the Portuguese also introduced Christianity to Thailand.

To learn more about this unique sweet, I pay a visit to Thanusingh, a family bakery that has been making khanom farang kutii jiin in the shadow of Santa Cruz Church for more than 200 years. Pong, a fifth-generation baker, and Thai of mixed European and Japanese descent, is one of the few people in Thailand still making this dessert, and explains how every effort is made to preserve the original recipe and methods. “The Portuguese tourists who come here recognize the cakes immediately,” explains Khun Pong of the sweet that has changed little in several centuries.

Khanom farang kutii jiin fresh from the oven.

To make khanom farang kutii jiin, duck eggs and sugar are beat at a very high speed until slightly stiff and peaked. Formerly this was done by hand using an improvised pulley system turning a wooden paddle, but today modern electric blenders do the job. Flour is then carefully folded in, and the mixture is poured into small hand-made metal trays. These are then baked in a modern, custom-made oven that recreates the effect of the original method of employing a bed of heated gravel topped with hot coals. When the cakes are done, I try a hot one, and find the cake dry and generally unremarkable, but to Ayuthaya-era Thais not familiar with bread or sweets, it must have been nothing short of a culinary revolution.

Khanom farang kutii jiin, a Thai snack of Portuguese origin, are still made using traditional methods.

Khun Pong goes on to mention that the Santa Cruz Church area is also known for other dishes almost certainly of Portuguese origin, including a dish of a roasted calf’s leg inserted with dried spices, and a hearty vegetable stew probably with origins in the Portuguese cozido, both of which are typically are only made during Catholic festivals nowadays. Portugal’s influence on Thai cooking is a unique culinary heritage, the result of a centuries old cultural exchange, that is both thriving, and in danger of dying out.

A nice view of Bangkok

This week's nice view is from the Dome at State Tower:

This is the Chao Phraya River just before it heads out to sea. Actually, most of Bangkok is behind you; what you see here is actually the province of Thonburi. The Dome is a conglomeration of two restaurants and a bar, and is arguably Bangkok's hottest place to eat right now. Haven't eaten there yet--only been up to take photos for a magazine--but hope to get there soon. Will let you know how it is.

Cornucopia

Today's Cornucopia column, written by our favorite Thai food expert, Suthon Sukphisit, concerns the Thai staple fish, plaa thoo, known in English as horse mackerel. Mr Sukphisit discusses the harvesting, history and uses of this fish, and describes some very delicious dishes that can probably be made at home as long as you can get your mits on the fish.

Fresh plaa thoo for sale at Phuket's morning market.

The direct link to the article doesn't seem to be working right now, so if you're interested in reading it, try going to the Outlook section and choosing the article title, "Thailand's favourite fish"--hopefully it will work by the time you get this.

Kai Yaang Sut Jai

Another day, another isaan (NE Thai-style) restaurant. This particular bad boy is located in the Or Tor Kor Market compound and is known for its kai yaang (grilled chicken), as the name suggests. We consumed this dish, but the shop was dark and the pic was crap, so I've decided not to include it here.

Other things we ate were tom saeb:

This is a sour/spicy soup popular in the NE of Thailand. "Saep" means spicy and sour at the same time, and this soup was deliciously tart. This one was based on tender pork joints, and had the unsual addition of lettuce and chinese celery in the broth.

We followed this with tam sua:

This is an isaan-style som tam, or papaya salad, with the addition of fermented rice noodles. The black bits are pickled field crabs; they are crushed up with the papaya in the mortar and pestle used to make the dish and are a very common ingredient, added more for flavor than anything else.

For the kid we ordered tam poo:

This is a milder, central-style papaya salad with crab and cashews. We told them to make it palatable for a kid, not spicy, and the result was sweet enough to be a dessert. I couldn't eat it but Nong Paeng liked it.

This is her demonstrating the proper way to eat sticky rice, ie., with the fingers:

One more thing worth mentioning about this place it's also probably the loudest restaurant I've ever eaten at. The staff are terribly unorganized and compensate by screaming orders at each other. It's really quite unbelievable, both in terms of volume and also in terms of what people are willing to subject themselves to in order to eat good food!

Real Lao

Just got back from four days in Singapore for the World Gourmet Summit. More on that later... In the meantime, I've been wanting to post an article of mine that ran in Intermezzo magazine. The piece concerns the food of Laos, an interesting cuisine, and a current topic at eGullet. Enjoy!

Spicy, Salty, Sour and Sweet: My Second Taste of Laos (Intermezzo Volume No. 5, Issue 13)

In 1998, as a twenty-year-old junior at the University of Oregon, I received a scholarship to visit Laos with a group of students from various Southeast Asian countries. At that point the country had only recently opened its doors to international tourism, and when I arrived I had the distinct impression that I was somewhere unknown and unvisited by the outside world. Since my college years, I have spent most of my time living and working in Thailand. I have eaten countless amazing Thai dishes, and tasted the foods of nearly every country in Asia. Yet I'm constantly reminded of the food of Laos, and recently decided to revisit the places and tastes that proved to be so eye-opening to me as a student.

Tam baak hung, a tart salad of unripe papaya, eggplant and tomatoes, is a favorite meal in Laos.

What I ate in Laos eight years ago was so unlike anything that I had ever tasted before that it truly grabbed my attention. Several of my culinary experiences still remain vivid to this day, such as my first time eating sticky rice, being faced with an intimidating dish of raw beef laab, and eating a papaya salad so spicy I nearly fainted. Every meal seemed an adventure, the food being both unusual and exciting, and after all this I was shocked when, after arriving home, I heard Lao food brushed off as “like Thai food but less spicy”.

Beer Lao is considered by many to be the best beer in Southeast Asia.

The food of Laos is based on fresh ingredients and boasts assertive flavors. Being a poor, mountainous, landlocked country has had an impact on the cuisine that makes Lao cuisine completely distinct from its big brother to the West. To begin with, that most important of Asian staples, rice, is in Laos, very different than that of Thailand. Rather than fragrant, long-grained rice, the staple carb of Laotians is short-grained “sticky rice” known as khao niaow. And as Laos is fully landlocked, freshwater fish is an immensely important staple, as is game (including deer, wild birds, lizards and other ahaan paa, or "jungle food"). And that symbol of Chinese culinary imperialism, the wok, has made little inroad in Laos, where much of the food is grilled or prepared in soups rather than fried.

I begin my journey in Vientiane (pronounced “wieng jan”), the capital of the Lao People’s Democratic Republic. Although it’s only a short bridge crossing over the Mekong River from Thailand, Vientiane feels a world, and a generation away. Upon arrival in the city, one is greeted by crumbling colonial-era villas and towering shade trees, a palpably different experience from the largely characterless, concrete cities of Thailand. Schoolgirls wearing the Lao national costume, a long embroidered skirt called the phaa sin cycle by on bicycles, and monks wrapped in bright orange sweep leaves in front of Buddhist temples. The capital of Laos is essentially a sleepy, dusty town on the banks of the Mekong, undoubtedly how Thailand was a generation ago, and much of the isolation of the past 30 years has served to preserve a culinary heritage that, even today, is still very much intact.

Fresh lemongrass is a common ingredient in Lao cooking.

Upon arrival in Vientiane, I proceeded directly to the banks of the Mekong River to begin my culinary reeducation by sampling what is undoubtedly the most quintessential of Lao dishes, tam baak hung. Consisting of strips of shredded green, unripe papaya, sliced tomatoes, lime, garlic, and fish sauce all ground together with a mortar and pestle, this tart “salad” is a relatively simple but delicious meal. The deep wooden mortar used to make tam baak hung is ubiquitous in every part of Laos, and is almost always wielded by women. Some cooks pound aggressively, as if punishing the papaya, the mortar and the pestle at once, while others use the mortar and pestle more as mixing tools, gently coaxing the ingredients together. Regardless of how it is done, the bell-like hollow thud that resonates when the dish is being prepared is recognizable enough to make one’s mouth water. One particular element that makes a tam baak hung particularly Lao is the use of chilies. Despite what others may say, the majority of Laotians actually do like their food hot, and I still wince when I recall a dish of tam baak hung I had in 1998 that was so spicy, that after the almost intolerable initial heat, I began to feel an intense chili-induced “high”, and stumbled back to my hotel room in a near-stupor.

The spiciness of chilies is, along with sour, sweet and salty, one of the four essential tastes that makes up Lao cuisine. Sour flavors typically come from the use of lime juice or crushed tamarind pulp, and a dish’s sweet taste might be the result of cane or palm sugar. Saltiness is usually obtained through generous use of paa daek, a mud like, unpasteurized fermented fish sauce essential to Lao cooking. The use of paa daek lends Lao food a certain earthy flavour, not to mention the fact that many Lao people still prefer to eat ahaan paa, game taken from the jungle. Lao food is also earthy in its tones, many of the dishes brown from the use of ingredients such as mushrooms or paa daek, or green from the addition of fresh herbs.

French-style baguettes for sale in Luang Prabang.

As with most countries in Asia, the staple food of the Lao people is rice. Not fluffy steamed rice, as in the vast majority of Asia, but rather, heavy, glutinous “sticky rice”. This form of rice grows well in Laos’s relatively high mountain valleys, and is prepared by being steamed over boiling water in wicker baskets, rather than by being immersed in water. In Lao households, sticky rice is often prepared in the morning then left in a permeable wicker container for the rest of the day, to be consumed with all meals. This container is known as a katip, and individual serving sizes, often used in restaurants, make good souvenirs. Sticky rice is eaten using the hands, and is rolled into a ping-pong sized ball with the right hand, and dipped into soups and dips. Eating sticky rice in Laos was the first time in my adult life that I had ever eaten entire meals with my hands, and I remember finding it a liberating and delicious experience.

To truly get a feel for Lao food, it helps to see the ingredients in their raw form. This is best done at any of the morning markets that take place every day at nearly every town in Laos. With this in mind, on my second day in Vientiane I wake up early to visit the hectic talaat sao, or morning market. Making my way past piles of lemongrass, pink joints of galingale and neatly bound bunches of dill and coriander, I wander over to the meat section, where entire chickens are on display, and bored-looking vendors shoo flies away from pork meat. Despite being a poor country, the inhabitants of Laos are generally rich with food, and consume meat on a regular basis. Thus, along with tam baak hung and sticky rice, the third essential element of Lao food is ping kai, grilled chicken. Grilled foods rule in Laos, and can range from fish to pork skin, but grilled chicken is the most popular, and arguably the most delicious. Chickens are typically first deboned before being rubbed with a mixture of cilantro root, garlic, turmeric, and salt, and are then splayed on a bamboo rack and grilled over hot coals. The result is smoky and savory, and along with tam baak hung and sticky rice, forms a complete Lao meal.

After a few days in Vientiane, I continue my culinary tour by traveling north to the former royal capital of Laos, Luang Prabang. Situated on a finger of land between the Mekong and Khan Rivers, Luang Prabang was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site because of its pristine colonial-era and traditional Lao architecture. The city is one of the most pleasant and atmospheric places in Asia, if not the world, and is also where I had spent the majority of my time in Laos all those years ago.

I was eager to return to the places I had eaten in Luang Prabang, and made a point of making pho, Vietnamese-style noodle soup, my first meal upon arrival. Surprisingly for a landlocked, isolated country, there is a considerable amount of culinary influence from other countries, and pho is an example of this. However, Lao pho, unlike the beef-based Vietnamese original, is typically served with pork or buffalo meat. The soup is served with side of fresh herbs including Thai basil, sawtooth coriander, and the fragrant young mint leaves particular to Laos, as well as limes, pickled vegetables, chili paste, and deep-fried crispy rice cakes. It is this variety of condiments that makes pho such an individual eating experience. Almost instinctively, I added the herbs, squeezed my limes dry, crumbled the rice cake, mixed the soup, and the tart, herblike scent that resulted took me immediately back to my first time in the country.

Starfruit for sale in Vientiane.

Laos was part of French Indochina for more than 50 years, and other than Vietnamese food, along with French rule came certain inseparable European culinary traditions, including bread. It was in Luang Prabang where I first came in contact with khao ji, French-style baguette sandwiches that arrived in Laos via the Vietnamese. Using freshly baked bread, khao ji are often consumed at breakfast, the bread somehow always able to stay crisp and flakey despite the humidity, and spread with a variety of ingredients usually revolving around a form of pork-liver pate (no doubt also vestige of French influence) or the ubiquitous Vache Qui Rit cheese spread.

It is a desire for bread and yet another French legacy that impels me to wake up early on my first morning in Luang Prabang. My memory serves as my guide to a ramshackle mélange of benches and chairs known as Pasaneyom Lao Coffee. I am here to sample what must be the most ubiquitous French culinary legacy in Laos, coffee. The Laotians took this unfamiliar product and created their own method of brewing it, pouring hot water through a small baglike filter filled with coffee grinds. The resulting thick liquid is served small tumblers with sweetened condensed milk and followed by a “chaser” of green Chinese tea. The people of Laos also produce coffee, at one point the country’s beans, mostly grown in the southern part of the country, being among the costliest in the world.

Another remnant of foreign influence is the country’s beer. Laos is also home to what is considered by many to be the best beer in South East Asia, Beer Lao. Despite formerly being a monopoly (and thus not necessarily obliged to produce a good product), the state-owned Lao Brewing Company produces a fresh-tasting, hoppy lager-style beer, which when served ice-cold on a hot Lao day, is somehow even more refreshing than water. Beer in Laos is typically served with ice cubes, and sometimes, during the sweltering months of summer, bottles of Beer Lao are served wun, meaning that the beer is so cold it has reached a slushy, near frozen state.

While in Luang Prabang I was eager to sample the town’s unique local food, a cuisine that differs substantially from that of the rest of Laos. As in much of the country, the best and sometimes only place to sample local cuisine is at the evening market. Here freshly made curries, soups and salads are dished up to take home along with steaming hot sticky rice. In Luang Prabang, grilled Mekong River fish and ping kai can also be found, as well as a variety of jaew, a kind of chili-based “dip” eaten with sticky rice and vegetables. A particular specialty of Luang Prabang is jaew bong, roasted dried chilies pounded with garlic, shallots and buffalo skin. Jaew bong is traditionally eaten with sticky rice and paper-thin crispy sheets of dried Mekong river weed called khai phaen. After some deliberation, I buy both of these, as well as a bottle of ice-cold Beer Lao, and return to my hotel for a final celebratory meal. The occasion? I have tasted Laos again.

Lao eggplants come in a variety of shapes and colors.

Recipes:

Khao Niaow

Sticky Rice

Serves 4

In Laos, sticky rice is traditionally steamed in a cone-shaped bamboo basket called a huat The rice is placed over an aluminum pot designed to fit snugly with the huat. If you can find these at an Asian market, go ahead and use them, otherwise this recipe is adapted for use with a two-piece pasta pot.

2 cups Thai sticky rice

5 cups water

1. Soak sticky rice in water for four hours. Drain water and set rice aside.

2. Add water to a pasta pot until it is slightly below the bottom of the strainer. Line the removable strainer with cheesecloth, and add the sticky rice.

3. Insert strainer, tightly replace the lid, and bring water to a boil over high heat. Steam rice for 20 minutes, until grains are soft but firm.

4. When rice is done, remove cheesecloth with rice and open on a countertop, using a wooden spatula to spread the rice out flat, and let sit for five minutes.

5. Keep rice in a permeable container, such as a colander covered with cheesecloth, until needed, and serve warm, or at room temperature.

Tam Baak Hung

Papaya Salad

Serves 4

To shred the papaya, peel the papaya first, then use a cheese grater with large holes. Alternatively, for more hearty slices of papaya, use a sharp knife to dash several lengthwise cuts into the green, unripe papaya, then, using a knife or potato peeler, shave off strands of the papaya. The strips of papaya should be roughly cardboard thick and more or less as wide as a finger. In Laos, tam baak hung is made using a mortar and pestle, but as most people in the West don’t use these tools, this recipe is adapted for use with a sturdy bowl. In terms of seasoning the tam baak hung, in Laos this dish is made to taste, so if you prefer spicy, then add a few more chilies. If you dislike sour, then don’t add all of the lime juice and tamarind pulp. To this extent I have suggested adding only half of the seasoning ingredients initially, then adding the remainder to taste.

1 tablespoon tamarind pulp

5+ Thai chilies

2 cloves of garlic

3 cups shredded unripe papaya

5 cherry tomatoes halved

2 golfball-sized green or yellow Thai eggplants

1 tablespoon lime juice

3 tablespoons fish sauce

1 tablespoon of palm sugar (or white sugar)

1. Prepare tamarind by mashing the pulp up with 1/4 cup of warm water. Strain the resulting liquid and set aside.

2. Roughly chop chilies and garlic and smash with the broad side of a knife.

3. In a large bowl insert chili and garlic mixture and the shredded papaya and tomatoes. Slice the Thai eggplant directly into the bowl, and mix and grind all the ingredients using the bottom of a large wooden spoon, for about 20 seconds. The idea here is to gently bruise the papaya so that the other flavors will penetrate.

4. Add half of the tamarind, lime juice, fish sauce and sugar, and grind again. Taste for a balance of spicy, sour, sweet and salt, and add additional lime juice, fish sauce or sugar as needed.

5. Serve immediately with sticky rice.

Ping Kai

Lao-Style Grilled Chicken

Serves 4

In Laos entire chickens are typically deboned and splayed on bamboo racks before being grilled. For simplicity this recipe uses a whole chicken that has been jointed. Another option would be to use six chicken thighs.

1 chicken, jointed and cut into parts

2 tablespoons of salt

3 tablespoons of chopped cilantro roots

1/2 tablespoon peppercorns

4 tablespoons of chopped garlic

1 teaspoon turmeric powder

1 teaspoon fish sauce

1. Rub chicken parts with salt and set aside for 20 minutes to draw out any unpleasant juices.

2. In the meantime, using a mortar and pestle or food processor, finely grind cilantro roots, peppercorn, garlic and turmeric powder until a thick paste results. Stir in fish sauce.

3. Wash chicken pieces, pat dry, and coat with the paste. The previous steps can be done the day before and the chicken left to marinade in the paste overnight. Otherwise allow chicken to marinade in the paste at least 30 minutes before grilling.

4. Grill over a well-oiled grill on medium heat, turning every 10 minutes, until finished.

A good read

For those of you interested in reading more about Thai food, I encourage you to take a look at Suthon Sukphisit's weekly column, Cornucopia, which runs every Saturday in the Outlook section of the Bangkok Post. Suthon is a retired writer with the Post, and now spends most of his time writing about food and travel. The guy is a virtual expert on Thai food, and I look forward to reading his column every Saturday. We haven't yet met, but have exchanged emails, and I hope to take him out for some good Thai food at some point in the near future! Today's piece is actually about the food of Yunnan, a place with a very interesting local cuisine. I'll try to post a link to his piece every Saturday, although I think the links will eventually expire.

A Cool Lunch

Been cooking like a madman lately, revising recipes and taking photos for my book on southern Thai food. I love cooking, so this is fun for me. The only bad part is the weather. It's April here in Bangkok, which is the hottest month. Most of the time spent in my kitchen I'm literally dripping with sweat, so today I decided to make something cool:

The red are pieces of chilled watermelon, and the topping an odd but delicous mixture of dried fish, sugar and deep-fried shallots. This is an old-school Thai dessert I first had at David Thompson's dinner at cy'an. He gave me the recipe, which involves taking plaa chon daed diaow, a kind of semi-dried freshwater fish, and roasting or grilling it until dry. You then pick the flesh apart and grind it up in a mortar and pestle with some sugar. For the shallots you simply thinly slice a bunch of shallots and fry them in oil until they become dark and crispy. Let them drain on several changes of paper towels, mix with the fish mixture, and sprinkle over the watermelon!

Northern Exposure

Found myself in the right part of town at the right time and got my mits on some nice northern-style Thai food today. The right part of town is Viphavadee, the right time lunch, and the right restaurant, Khao Soi Faa Haam. This is actually the name of the most famous khao soi--a northern-style curry noodle dish--restaurant up in Chiang Mai. I was up there about a year ago interviewing the owner for an article on khao soi, when I learned that they also have a branch here in Bangkok, and have been enjoying it on a regular basis. Khao soi is getting a lot of attention recently, with a fun thread at eGullet, and Chubby Hubby also featuring some pics in a recent post.

I went to the restaurant with the obvious desire to have a bowl (or two) of khao soi, but in the time-honored tradition of Thai ill-preparedness, they were temporarily out (it was, after all, 12:30!), and would I mind waiting? This was actually a blessing in disguise, as it allowed me to stray from the well-eaten path and order something different for once. This Something Different was khanom jeen naam ngiaow:

The dish is of Shan/Thai Yai origin, and is actually quite similar to a spicy, sour spaghetti. It is made by frying ground pork in curry paste with small, sour tomotoes. Water and pork spareribs are added, and topped with everybody's favorite, cubes of coagulated chicken blood. This is then served over fermented rice noodles. Possibly the best part of the dish is the deep-fried crispy garlic.I've eaten this dish heaps of times--and even make a mean version myself--but this was the first time I'd eaten it here, and I'll certainly have it again.

By the time I finished my nam ngiaow they were finally done making the khao soi:

I usually order beef khao soi, but they were out (!) today, so I had to settle for the chicken. Still very good, but this was probably the richest bowl I've ever consumed--I couldn't even finish all of it!

Thai with Thompson and Thanongsak

Was fortunate enough to have lunch with David Thompson, Head Chef of London's Nahm, and author of a big fat book on Thai cooking, and his partner, Thanongsak. I first met David when I interviewed him for an article on Michelin-starred chefs visiting Bangkok. We got to talking about Thai food and mentioned that there was a place near my house that makes an excellent khao mok plaa, fish biryani. He was intrigued, and yesterday we finally met up again, this time at the aforementioned restaurant.

The place in question is Yusup (probably a Thai corruption of the Arabic name Yusuf), a Thai-Muslim restaurant located along the Kaset-Nawamin highway in northern Bangkok. I had unknowingly driven past this place literally thousands of times before a friend recommended it to me. After my first visit I soon became a regular customer, and have been wanting to take people there for ages.

David and I started with the requisite khao mok plaa:

Not a particularly evocative pic--was focusing more on eating and chatting about Thai food, but you get the idea. For those of you not familar with this dish, biryani, called khao mok in Thai, is rice cooked with spices and meat, which in Thailand is almost always chicken. It's an amazing concept, but, as David mentioned, never seems to fulfill its potential. Most of the time it's just rice colored yellow with turmeric (or food coloring) with some crap chicken thrown on it. The good men and women at Yusup however, know what's going on and load their version with spices, peas, minced carrots and fresh herbs. Other than fish they also have beef, goat, and the ubiquitous chicken versions.

This was accompanied by sup haang wua, oxtail soup:

A Thai-Muslim speciality, this soup is both mouth-puckeringly sour (from lime juice and tamarind) and rich (undoubtedly the result of all that marrow and bones), and the oxtail has been slow-stewed until fall-apart tender. Amazing stuff.

Thanongsak wisely ordered something outside of the two dish repertoire that I tend to stick to and chose matsaman nuea, "Muslim" curry with beef with roti, fried dough:

I found the matsaman to be one of the best coconut milk-based curries I've had in a long time; smooth, not too sweet, savory, and with a pleasant taste of coconut that, oddly enough, isn't usually found in these curries. The roti, on the other hand, were mediocre--not nearly as crispy and fresh as they should be.

And finally, after all this nosh, David shocked us all by ordering a bowl of kwatiao kaeng, "curry noodles:

This is a dish that one rarely sees around, and is more similar to the Malaysian laksa than anything Thai. David mentioned that he liked it the more he ate it:

but in the end commented that it could have used a final swirl of coconut cream to smooth it out.

Bangkok B&W Episode 3

Was in the Tha Phra Chan area today, an old Bangkok neighborhood along the Chao Phraya with lotsa cool stuff to see and eat.

This woman is making mataba, savory filled "pancakes":

Maharat Road, running paralell to the river, is a virtual open air market, and this guy is selling the most common item, Buddha amulets:

A line of tuk-tuks along the same street:

This was taken on a ferry boat crossing the river a bit downstream at Rajanee Pier:

A nice view of Bangkok

This pic was taken last night from D'Sens, the French restaurant located at the top of the Dusit Thani Hotel:

For the most part, Bangkok is a big ugly intimidating city, but there are some nice corners, views and neighborhoods here and there. This shot is over looking the BTS line, with Lumphini Park on the right, and Bai Yok, Thailand's tallest building, in the upper left hand corner.

I'm currently doing a piece on restaurants with nice views, so I'll try to include more pics like this. In terms of views, I would really recommend D'Sens, having nearly 360-degree views over the city from its 23rd-floor cockpit-like dining room. (The restaurant also has the most amazing bathrooms in the city, the men's urinal being a floor-to-ceiling window that gives one the sensation of literally pissing on the city! Great therapy for those fed up with urban life.)

Khrok Thong

Khok thong ("Golden Mortar") is the name of a popular isaan (North-Eastern Thai) restaurant near my house. For those of you not familar with ahaan isaan, this cuisine has a lot in common with the food of Laos, just over the Mekong River. This means a lot of grilled dishes, salads and soups, with very little of the Chinese-style fried stuff seen in Bangkok and southern Thailand. Additionally, people in isaan tend to eat glutinous or "sticky" rice with all their meals.

A staple of ahaan isaan is som tam, a type of "salad" made of unripe papaya pounded up in a mortar and pestle usually with green beans, tomatoes, chilies, lime juice, fish sauce, garlic and sugar. Today we ordered tam sua:

This is a particular kind of som tam that includes khanom jeen, fermented rice noodles. This may seem an odd combination, but the noodles do a great job of mellowing out the dish, which is typically very spicy. The yellow bits are the peel of ma kok, a kind of sour fruit (I think it's called Chinese olive, or something similar to that) that adds a tart flavor to the dish. (Ma kok, incidentally, is the origin of the name Bangkok, meaning a plain where lots of ma kok trees are found.) I'd venture to say that right now som tam is probably the most popular food in the country; EVERYBODY loves the stuff, and it can be found on virtually every street corner.

Another isaan favorite is khor moo yaang, "grilled pork neck":

This dish takes the fatty fatty meat (sometimes also known as the "collar") grilled and typically served with a spicy/sour/salty dip.

Isaan food is always taken with khaao niaow, "sticky rice":

which is eaten with the hands and rolled in a small ball before being dipped in any of the dishes present. The container its served in is known as a katip and is meant to hold the rice while at the same time allowing heat and moisture to escape. Unfortunately most restaurants put the rice in a plastic bag, which really defeats the purpose and often results in a mushy, sticky mess. Fortunately that wasn't the case today.

And finally we had kaeng om plaa duk:

Kaeng om is a type of soup typically revolving around lots of veggies and fresh herbs. This one was loaded with cabbage, lemongrass, basil, and most prominently, dill (known in Thailand as phak chii lao, "Lao cilantro/coriander"). This kaeng om was of the plaa duk, catfish variety.

Sukiiiii!

Possibly the most popular restaurant meal among middle-class Thai is suki-yaki, the Japanese hot pot dish that Thai refer to simply as sukii. For those not familiar with the dish, it's basically a do-it-yourself meal that revolves around a cauldron of boiling broth. You order raw ingredients and cook them in the broth.

Like noodles, this is another one of those dishes that Thai people love that I never really cared for until somewhat recently. I really enjoy it now, as it revolves around my two faves: seafood and veggies, and is about as healthy as it gets.

There are several franchises serving suki in Thailand including MK, Coca and See Fah, but today we tried a new one, called simply, Hot Pot.

We like veggies so we ordered the veggie set:

We've got phak bung (the long green veggie), green onions, kheun chai (Chinese parsley), carrot slices, daikon slices, a few types of mushrooms, tofu, and in the back, glass noodles. We also ordered a few other, mostly fish-related, side dishes such as squid, fish, fish balls, and fish "noodles".

This is Khuat taking the first step: pouring the beaten eggs into the broth:

When the broth boils again, then we start piling the rest of our ingredients in:

Wait a few minutes until they're cooked, and dig in!

The Thai way to eat this is to take an ingredient out, and dip it in the sauce below before shoving it into the gob:

It's a largely sweetish/sourish sauce with sesame seeds and cilantro, and which is usually accompanied by a separate dish of optional minced garlic, minced chilies and limes to make it really Thai. I think the sauce is just OK, but Thai people really seem to love it. Personally I like to sip the broth, which I imagine is the Japanese way of eating sukii, but which nobody here seems to do.

In general, I felt that Hot Pot's take on the whole thing was very mediocre. It's really hard to do a bad job of suki--it really just depends on the quality of the ingredients--and in this case the seafood we ordered was obviously past its prime, and the veggies neither attractive nor fresh. Much better in my opinion is Coca, especially considering that they have a half-broth/half-tom yam cauldron, and lotsa fresh veggies and seafood.

Raan Rot Det

Raan Rot Det ("bold taste shop") is the name of a curry stall at Or Tor Kor market that I've been eating at for years:

The food isn't amazing, but it's consistently good, and there's an amazing variety of curries, fried dishes and soups:

I tend to order the same things, and here what I had last time I stopped by:

At 12:00 is a stir fry of tofu with ground pork and kheun chai, Chinese celery; at 3:00 is kaeng khii lek, a southern-style coconut curry that combines the bitter leaves of the khii lek tree and grilled fish; and at 6:00 phak khanaa kale/chinese broccoli fried with oyster sauce and barbecued crispy pork belly.

More Noodles

Casual readers of RealThai must get the impression I'm noodle obsessed. In fact, I hadn't hardly eaten noodles at all the first several years I worked here. I always found Thai noodle dishes too sweet, and the various pork/beef/fish balls that seem to accompany such dishes are, for the most part, shockingly nasty. In recent years I've opened up a bit and have found a few noodle dishes I really enjoy, including the topic of this entry, kwaytiao khae. I've mentioned this particular dish before here and here, and recently noticed a new shop not far from my house selling the stuff. Well, despite it's rather attractive appearance:

this was by far the worst bowl I've yet to encounter. If kwaytiao khae was served on board airplanes or in hospitals, this is what it would taste like. The broth was institutional and tasteless, and the various ball products tough, chewy and tasteless.

Khuat didn't have much better to say about her yen ta fo:

When I get a chance, I plan to feature the best kwaytiao khae I've had yet, which is sold virtualy on the side of the road in Chinatown. Please be patient.

Thai Muslim with Mike

Was recently fortunate enough to meet Michael Elliot, a Montreal-based food stylist (now there's an occupation that didn't exist 30 years ago!), fellow blogger, cool website owner, and fan of Thai food. Michael and friend were passing through Bangkok and we met up for lunch a few days ago. As I've done in the past when others have visited, I like taking people to a brilliant Thai Muslim place down near the Oriental Hotel. The restaurant, called (if I remember correctly) Muslim Home Cooking, is relatively new, and specializes in Indian-influenced Thai-Muslim cuisine.

We started with a speciality of Thai Muslim food, fish curry:

This Thai Muslim staple sees hearty "steaks" of fish (usually plaa insee, Spanish mackerel) in a thick, sour curry broth. Usually there a few vegetables thrown in for shits and giggles, in this case okra and tomato (sometimes also eggplant or green bananas).

This we followed with mutton spareribs in curry sauce:

I've never come across this dish in Thailand and assume it is Indian-Muslim in origin. It's a great dish; we finished every drop of the curry sauce, and really enjoyed the garnish of crispy deep-fried shallots.

As one usually does when eating Thai Muslim we skipped the rice altogether and instead took our curries with the cripy pancakes known as roti:

Other highly recommended dishes here include the khao mok (briyani), which is served with a raita (cucumber-yoghurt mixture), a sweet and sour sauce, and a savory eggplant dish. The restaurant is located virtually across the street from the French Embassy in the Haroon Mosque area.

More Myanmar

Spent another Saturday morning in the company of Daw Than Than Myint and John Parker eating Burmese food. This time it was mohinga:

a thick, fish-based broth that is often considered the national dish of Myanmar. The noodles used are similar to the fermented rice noodles known in Thailand as khanom jeen, and the broth fortified with ground fish, shallots/onions, and the edible soft pith from the innermost stalks of the banana tree. In Myanmar this is usually accompanied with the fresh veggies seen in the pic, as well as a kyaw, crsipy deep fried vegetables. Daw Than Than Myint claims this is the best mohinga in Bangkok.

Our Mohinga was taken with wetha lon kyaw, literally "fried pork balls":

ground pork mixed with herbs and spices and deep-fried. They are taken with the spicy/sour dipping sauce seen in the background. Personally, I found this a bit unusual, as the Burmese aren't real big meat eaters, and I can't recall having come across any dishes using pork in Myanmar. Perhaps it's some sort of adaptation made for Thailand?

ThaiDay: The Michelin Movement

The Michelin Movement (ThaiDay, 31/03/06)

World-class chefs are in high demand in Bangkok these days. What do the chefs think of their stardom?

Gerald Passedat appears tired, and rightfully so: just a few days earlier he was probably happily filleting fish in the kitchen of Le Petit Nice, his two Michelin-star restaurant in Marseilles, southern France. Today the chef is in Reflexions, the Plaza Athenee Bangkok’s French restaurant, trying to balance answering the questions of the local press with preparing a six-course meal for more than 30 people. This is Passedat’s first time in Thailand, not traditionally a stopover on the route of Michelin-starred chefs, and he’s obviously trying to make the most of it. “Asia is important for us [chefs],” he explains. “We’ve got to travel and see what’s happening, new types of cooking and ingredients.”

Important indeed. This month alone, chefs from no fewer than six Michelin-starred restaurants are paying visits to Bangkok’s top hotel restaurants. From David Thompson, Head Chef of London’s Nahm, the only Thai restaurant ever awarded a Michelin star, to Pierre Gagnaire, Head Chef of the eponymous three-starred Paris restaurant considered by many as one of the finest in the world, Bangkok has seemingly been inundated by this virtual constellation from the culinary stratosphere.

This interest in high-end dining is hardly new however. Bangkok’s first effort in this area began in earnest back in 2000 with the initiation of the World Gourmet Festival. This event brought in chefs from virtually every corner of the world, and was generally considered a critical and financial success. The event has continued to be held every year since, and in late 2005, the concept was taken to an extreme with the Epicurean Masters of the World. This event saw 10 chefs with a total of 19 Michelin stars brought together under one roof—something that rarely occurs even in Europe. The Michelin accolades of the chefs involved were liberally touted during this event, setting a precedence that will be difficult to follow, and perhaps also whetting the appetite of Bangkok diners to crave the occasional star with their meal.

The brothers Pourcel prepare their dishes at D'Sens at the Dusit Thani Hotel.

This month’s largely coincidental culinary deluge may well be the result of consumer demand, but it is also an illustration of the current trend for chefs to leave their comfort zones and be exposed to new influences. During this month I was fortunate enough to meet with some of the visiting chefs, and gained some interesting insights regarding Michelin stars, local ingredients, as well as the state of fine dining in Bangkok.

Two chefs who are no strangers to neither Asia nor Michelin stars are twin brothers, Jacques and Laurent Pourcel, of Le Jardin des Senses in Montpellier, France. Established in 1988, their restaurant quickly accumulated praise for its Asian-influenced Mediterranean cuisine, and at one point was awarded three Michelin stars. Since then, the Pourcels have used their acclaim and skills to establish successful restaurants not in the usual suspects of London and New York, but rather in Bangkok, Tokyo, Singapore and Shanghai.

Despite their obvious success, the topic of Michelin stars can be a touchy subject for the Pourcel brothers; after having held on to three stars for four years, in 2004 Le Jardin des Sens was downgraded to two, where it still remains today. With this in mind, I visit D’Sens, the restaurant in the Dusit Thani that the Pourcels oversee, and ask brothers what they feel are the negative and positive attributes of running a Michelin-starred restaurant. “The downside is that you’re seen as an “expensive” restaurant,” explains Laurent, “Although now you can find some places in the guide that are reasonable.” Jacques adds, “Nobody knows the judging standards. The system isn’t perfect, but the chefs who receive two stars are generally very good chefs and they deserve it.”

I mention the current flood of high-ranking chefs, and ask the brothers if they think that diners in Bangkok are really ready for such high-level dining. “Thais still expect traditional cuisine,” replies Jacques Pourcel. “They aren’t yet used to modern [cuisine], but there is still time to learn to appreciate new flavors and ingredients.” Ironically, in the case of the Pourcels, many of the “new flavors and ingredients” Jacques speaks of are actually staple ingredients in Thailand: passionfruit, coriander, tamarind and coconut milk are among the ingredients that the Pourcels have seamlessly integrated with traditional French cooking enough to make them unrecognizable even to Thais.

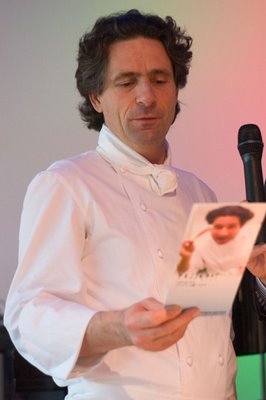

Two-star French chef Gerald Passedat.

French Chef Pierre Gagnaire, who is currently in residence at the Oriental’s Le Normandie, has never been to Bangkok before, but it was really only a matter of time. Gagnair is Head Chef of a restaurant in Paris considered among the finest in the world (and firmly clutching three Michelin stars), is the virtual inspiration for an entire school of gastronomy, and is considered by both chefs and diners alike to be among the finest chefs in the world.

Despite all this, Gagnaire is fully conscious of how tenuous culinary fame can be, having experienced a well-publicized financial collapse while running a previous three-starred restaurant. That restaurant folded, but Gagnaire eventually came back—in Paris of all places—and with his current restaurant, Pierre Gagnaire, again holds three stars. I ask Gagnaire if there’s a negative side to having a three-stars. “What’s bad is that you can lose them,” explains the chef. “Say you’ve got a film director, and he wins an Oscar. He can put it on his mantelpiece, it’s his for life,” explains Gagnaire through a translator. “With three stars, you don’t get them for life, you have to fight every day to keep them.”

Chef Pierre Gagnaire at the Oriental.

Gagnaire is certainly willing to fight, and does this by challenging diners with new flavors and textures (he calls them “disturbing minor details” or “multi-sensory hits”). I ask him if he thinks diners in Bangkok are ready for food of this level. “When it’s being done in a sincere and honest way, people don’t need to have a lot of references and knowledge about the cuisine to appreciate it,” explains the chef. However when traveling, Gagnaire admits that he feels less inclined to experiment. “It would be great to do something like a lemongrass infusion, but that’s not what people here want,” he explains.

Of all the chefs currently in town, Australian Chef David Thompson probably has the least enviable job of all: cooking an exclusively Thai meal for diners in Bangkok. This is nothing new to Thompson, who, after virtually stumbling upon Thai food more than twenty years ago, pursued this then-obscure school of cooking, eventually culminating in Nahm, his London restaurant, as of yet the only restaurant specializing in Thai cuisine to have been awarded a Michelin star.

Gerald Passedat's Loup Lucie, sea bass prepared in his grandmother's style.

Despite the unique accolade, Thompson is tangibly cynical about his star, and when I ask him about the benefits it has brought, he says straight faced, “It gets you into restaurants easily.” After laughing, he continues, “Any cook worth his fish sauce shouldn’t succumb to the idea of doing things for awards,” he explains. “If you start to become preoccupied with what other people think of you, or what awards you might garner, then you start to lose the point of why you’re doing it in the first place.”

I ask Thompson, who is currently in Bangkok preparing his take on Thai food at the Metropolitan Hotel’s cy’an, if he feels that Thais are becoming more sophisticated in their dining tastes. He replies, “I think it’s concomitant with the incredible boom that’s happened in this country, where people are becoming more affluent and wish to display their affluence. Thais have always been a status conscious society, and this is yet another way to display that.”

Despite the media attention and consumer interest, for most hotels, hosting a Michelin-starred chef is not necessarily a profitable venture. “For us it’s a tradition,” explains Konstantino Blokbergen, Director of Food & Beverage of the Oriental Hotel, whose restaurant, Le Normandie, has been hosting three-star chefs for almost 20 years. “But there is a cost associated with it. Financially, we try to break even, but it’s not done to make money. It’s an investment meant to last. It brings customers back.” In any event, it seems an investment that many hotels are willing to make, and with rumours of a possible Michelin Guide to Asia in the air, can also be seen as a sign of greater things to come.

Back at Reflexions, two-star chef, Gerald Passedat is posing for photos and trying his best to look cheerful. Earlier I had a chance to ask him how important getting the third Michelin star is to him. “When you have three [stars] you can open restaurants anywhere in the world and do whatever you want,” he explains. “But naturally, my goal is simply to make the customers happy.” Judging by the reaction from Bangkok’s diners, I would say that Passedat and his colleagues have been, without a doubt, successful in this area.

Guide to the Guide

The Guide Michelin, the source of all the stars, and undoubtedly the most influential restaurant guide in the world, started with practical beginnings. Introduced in 1900 by Andre Michelin, head of the eponymous tyre company, the guide was meant to assist motorists by listing lodging and restaurants, as well as provide information on mechanics, garages and bathrooms. In 1923 the guide began to review restaurants independent of accommodation, and in 1926 the star rating system was introduced, in which a star symbol was shown next to restaurants “noted for their fine cuisine”. In the 1930’s the star system was expanded to include the two and three-star system that still exists today.

The Red Guide, as the book is often called, covers 10 countries, mostly in Europe, although there is now a guides for New York City. Although much of the prestige of receiving a Michelin star is often associated with the chef, the prize is actually given to the restaurant, thus it is slightly inaccurate to describe someone as a “Michelin-starred chef”. Of the more than 5,000 restaurants reviewed in the 2004 UK and Ireland Guide alone, only 11 received 2 stars (“excellent cooking, worth a detour”) and 3 received three stars (“exceptional cuisine, worth a special journey”), making the stars very elusive indeed.

Despite the prestige associated with the stars, in recent years Michelin Guide has been subject to a fair amount of controversy. The book is regarded by many as being far too influential, and in 2003 a well-known French chef committed suicide, allegedly due to concerns that his restaurant was to be downgraded by the guide. In 2004 a former Michelin reviewer wrote a book describing the review standards as lax, and the Michelin inspectors are sometimes regarded as having a French bias.