The Michelin Movement (ThaiDay, 31/03/06)

World-class chefs are in high demand in Bangkok these days. What do the chefs think of their stardom?

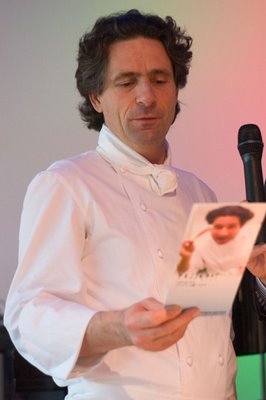

Gerald Passedat appears tired, and rightfully so: just a few days earlier he was probably happily filleting fish in the kitchen of Le Petit Nice, his two Michelin-star restaurant in Marseilles, southern France. Today the chef is in Reflexions, the Plaza Athenee Bangkok’s French restaurant, trying to balance answering the questions of the local press with preparing a six-course meal for more than 30 people. This is Passedat’s first time in Thailand, not traditionally a stopover on the route of Michelin-starred chefs, and he’s obviously trying to make the most of it. “Asia is important for us [chefs],” he explains. “We’ve got to travel and see what’s happening, new types of cooking and ingredients.”

Important indeed. This month alone, chefs from no fewer than six Michelin-starred restaurants are paying visits to Bangkok’s top hotel restaurants. From David Thompson, Head Chef of London’s Nahm, the only Thai restaurant ever awarded a Michelin star, to Pierre Gagnaire, Head Chef of the eponymous three-starred Paris restaurant considered by many as one of the finest in the world, Bangkok has seemingly been inundated by this virtual constellation from the culinary stratosphere.

This interest in high-end dining is hardly new however. Bangkok’s first effort in this area began in earnest back in 2000 with the initiation of the World Gourmet Festival. This event brought in chefs from virtually every corner of the world, and was generally considered a critical and financial success. The event has continued to be held every year since, and in late 2005, the concept was taken to an extreme with the Epicurean Masters of the World. This event saw 10 chefs with a total of 19 Michelin stars brought together under one roof—something that rarely occurs even in Europe. The Michelin accolades of the chefs involved were liberally touted during this event, setting a precedence that will be difficult to follow, and perhaps also whetting the appetite of Bangkok diners to crave the occasional star with their meal.

The brothers Pourcel prepare their dishes at D'Sens at the Dusit Thani Hotel.

This month’s largely coincidental culinary deluge may well be the result of consumer demand, but it is also an illustration of the current trend for chefs to leave their comfort zones and be exposed to new influences. During this month I was fortunate enough to meet with some of the visiting chefs, and gained some interesting insights regarding Michelin stars, local ingredients, as well as the state of fine dining in Bangkok.

Two chefs who are no strangers to neither Asia nor Michelin stars are twin brothers, Jacques and Laurent Pourcel, of Le Jardin des Senses in Montpellier, France. Established in 1988, their restaurant quickly accumulated praise for its Asian-influenced Mediterranean cuisine, and at one point was awarded three Michelin stars. Since then, the Pourcels have used their acclaim and skills to establish successful restaurants not in the usual suspects of London and New York, but rather in Bangkok, Tokyo, Singapore and Shanghai.

Despite their obvious success, the topic of Michelin stars can be a touchy subject for the Pourcel brothers; after having held on to three stars for four years, in 2004 Le Jardin des Sens was downgraded to two, where it still remains today. With this in mind, I visit D’Sens, the restaurant in the Dusit Thani that the Pourcels oversee, and ask brothers what they feel are the negative and positive attributes of running a Michelin-starred restaurant. “The downside is that you’re seen as an “expensive” restaurant,” explains Laurent, “Although now you can find some places in the guide that are reasonable.” Jacques adds, “Nobody knows the judging standards. The system isn’t perfect, but the chefs who receive two stars are generally very good chefs and they deserve it.”

I mention the current flood of high-ranking chefs, and ask the brothers if they think that diners in Bangkok are really ready for such high-level dining. “Thais still expect traditional cuisine,” replies Jacques Pourcel. “They aren’t yet used to modern [cuisine], but there is still time to learn to appreciate new flavors and ingredients.” Ironically, in the case of the Pourcels, many of the “new flavors and ingredients” Jacques speaks of are actually staple ingredients in Thailand: passionfruit, coriander, tamarind and coconut milk are among the ingredients that the Pourcels have seamlessly integrated with traditional French cooking enough to make them unrecognizable even to Thais.

Two-star French chef Gerald Passedat.

French Chef Pierre Gagnaire, who is currently in residence at the Oriental’s Le Normandie, has never been to Bangkok before, but it was really only a matter of time. Gagnair is Head Chef of a restaurant in Paris considered among the finest in the world (and firmly clutching three Michelin stars), is the virtual inspiration for an entire school of gastronomy, and is considered by both chefs and diners alike to be among the finest chefs in the world.

Despite all this, Gagnaire is fully conscious of how tenuous culinary fame can be, having experienced a well-publicized financial collapse while running a previous three-starred restaurant. That restaurant folded, but Gagnaire eventually came back—in Paris of all places—and with his current restaurant, Pierre Gagnaire, again holds three stars. I ask Gagnaire if there’s a negative side to having a three-stars. “What’s bad is that you can lose them,” explains the chef. “Say you’ve got a film director, and he wins an Oscar. He can put it on his mantelpiece, it’s his for life,” explains Gagnaire through a translator. “With three stars, you don’t get them for life, you have to fight every day to keep them.”

Chef Pierre Gagnaire at the Oriental.

Gagnaire is certainly willing to fight, and does this by challenging diners with new flavors and textures (he calls them “disturbing minor details” or “multi-sensory hits”). I ask him if he thinks diners in Bangkok are ready for food of this level. “When it’s being done in a sincere and honest way, people don’t need to have a lot of references and knowledge about the cuisine to appreciate it,” explains the chef. However when traveling, Gagnaire admits that he feels less inclined to experiment. “It would be great to do something like a lemongrass infusion, but that’s not what people here want,” he explains.

Of all the chefs currently in town, Australian Chef David Thompson probably has the least enviable job of all: cooking an exclusively Thai meal for diners in Bangkok. This is nothing new to Thompson, who, after virtually stumbling upon Thai food more than twenty years ago, pursued this then-obscure school of cooking, eventually culminating in Nahm, his London restaurant, as of yet the only restaurant specializing in Thai cuisine to have been awarded a Michelin star.

Gerald Passedat's Loup Lucie, sea bass prepared in his grandmother's style.

Despite the unique accolade, Thompson is tangibly cynical about his star, and when I ask him about the benefits it has brought, he says straight faced, “It gets you into restaurants easily.” After laughing, he continues, “Any cook worth his fish sauce shouldn’t succumb to the idea of doing things for awards,” he explains. “If you start to become preoccupied with what other people think of you, or what awards you might garner, then you start to lose the point of why you’re doing it in the first place.”

I ask Thompson, who is currently in Bangkok preparing his take on Thai food at the Metropolitan Hotel’s cy’an, if he feels that Thais are becoming more sophisticated in their dining tastes. He replies, “I think it’s concomitant with the incredible boom that’s happened in this country, where people are becoming more affluent and wish to display their affluence. Thais have always been a status conscious society, and this is yet another way to display that.”

Despite the media attention and consumer interest, for most hotels, hosting a Michelin-starred chef is not necessarily a profitable venture. “For us it’s a tradition,” explains Konstantino Blokbergen, Director of Food & Beverage of the Oriental Hotel, whose restaurant, Le Normandie, has been hosting three-star chefs for almost 20 years. “But there is a cost associated with it. Financially, we try to break even, but it’s not done to make money. It’s an investment meant to last. It brings customers back.” In any event, it seems an investment that many hotels are willing to make, and with rumours of a possible Michelin Guide to Asia in the air, can also be seen as a sign of greater things to come.

Back at Reflexions, two-star chef, Gerald Passedat is posing for photos and trying his best to look cheerful. Earlier I had a chance to ask him how important getting the third Michelin star is to him. “When you have three [stars] you can open restaurants anywhere in the world and do whatever you want,” he explains. “But naturally, my goal is simply to make the customers happy.” Judging by the reaction from Bangkok’s diners, I would say that Passedat and his colleagues have been, without a doubt, successful in this area.

Guide to the Guide

The Guide Michelin, the source of all the stars, and undoubtedly the most influential restaurant guide in the world, started with practical beginnings. Introduced in 1900 by Andre Michelin, head of the eponymous tyre company, the guide was meant to assist motorists by listing lodging and restaurants, as well as provide information on mechanics, garages and bathrooms. In 1923 the guide began to review restaurants independent of accommodation, and in 1926 the star rating system was introduced, in which a star symbol was shown next to restaurants “noted for their fine cuisine”. In the 1930’s the star system was expanded to include the two and three-star system that still exists today.

The Red Guide, as the book is often called, covers 10 countries, mostly in Europe, although there is now a guides for New York City. Although much of the prestige of receiving a Michelin star is often associated with the chef, the prize is actually given to the restaurant, thus it is slightly inaccurate to describe someone as a “Michelin-starred chef”. Of the more than 5,000 restaurants reviewed in the 2004 UK and Ireland Guide alone, only 11 received 2 stars (“excellent cooking, worth a detour”) and 3 received three stars (“exceptional cuisine, worth a special journey”), making the stars very elusive indeed.

Despite the prestige associated with the stars, in recent years Michelin Guide has been subject to a fair amount of controversy. The book is regarded by many as being far too influential, and in 2003 a well-known French chef committed suicide, allegedly due to concerns that his restaurant was to be downgraded by the guide. In 2004 a former Michelin reviewer wrote a book describing the review standards as lax, and the Michelin inspectors are sometimes regarded as having a French bias.