This may sound like a macabre title for blog post, but anybody who's been to a Buddhist funeral in Southeast Asia knows the events take a decidedly different form here. For starters, funerals in this part of the world are more like family reunions, and are generally festive, rather than dour in atmosphere. They can often last several days, depending on the family's budget. And most importantly, like much of life in Southeast Asia, they tend to revolve around food.

This may sound like a macabre title for blog post, but anybody who's been to a Buddhist funeral in Southeast Asia knows the events take a decidedly different form here. For starters, funerals in this part of the world are more like family reunions, and are generally festive, rather than dour in atmosphere. They can often last several days, depending on the family's budget. And most importantly, like much of life in Southeast Asia, they tend to revolve around food.

I learned this firsthand while walking the streets of Luang Prabang, in northern Laos. I was searching for images to illustrate an article on Lao food, when I came across a funeral entering its fifth day. A man of 82 had died, and directly in front of the house in which he grew up, his relatives and people who knew him had erected a tent and were busy cooking.

It truly was a communal affair, at least among the women, and everybody pitched in, including neighbours, neighbours' relatives visiting from America, and sometimes people who just happened to walk by:

Those not able to help in the more physical parts of preparation simply dished out the final product:

in this case, a thick coconut curry called khua kai.

When a meal, usually consisting of four different dishes, sides of fresh herbs and veggies, and sticky rice, was completed, the dishes were put on trays then laid out to be consumed:

Between meals everybody snacked on miang laao:

A variety of toppings ranging from pork crackling to garlic that are put in a leaf, topped with a salty/sour sauce, and popped in the mouth.

Among the dishes made in the three days I visited the funeral were an herb-filled omelet, a laap-like pork dish, and because it was in season, several dishes revolving around bamboo, including a clear soup (pictured at the top of this post), and a delicious stir-fry of crispy bamboo, egg and ground pork:

Below is the recipe for saem, an eggplant and pork dish that I was able to watch being made from beginning to end. I was told by the people making it that the dish can only be found in Luang Prabang, and is among a repertoire of dishes often served at funerals and other occasions.

I've failed to include amounts here simply because the women themselves didn't measure anything; like most recipes in this part of the world the cooking was done entirely by taste, feel and experience. The dish is pictured at the top of this post at about 4 o'clock, and below.

Saem: Pork and eggplant 'salad'

Making saem

-Boiled pork liver and belly, sliced thinly -Lao fish sauce (paa daek) -Rice cakes (khao khop) -Young, round purple eggplants (ideally w/out seeds), boiled until soft and peeled -Ground pork, boiled -Salt, MSG, dried chili powder -Green onion and cilantro, sliced finely -Sides: fresh mint, watercress, leafy pak boong, long beans, chilies and small purple eggplants.

Slicing pork liver for saem

1. Simmer fish sauce with some of the broth left over from boiling the pork liver and belly until reduced and fragrant. Strain and reserve. 2. Pound rice cakes in mortar and pestle until very fine. Remove. 3. Pound eggplant and ground pork in mortar and pestle until well blended. 4. Season to taste with Lao fish sauce, salt, MSG and chili. 5. Add pounded rice cake powder, liver and belly. Blend well. 6. Garnish with green onion and cilantro. 7. Serve with sides and sticky rice.

At Phonsavan's evening market.

At Phonsavan's evening market.

Known in these parts as khao niaow, I could eat this stuff all day. In Laos that's easier done than said. And at the moment, I'm also fortunate enough to witness the first stage in rice production:

Known in these parts as khao niaow, I could eat this stuff all day. In Laos that's easier done than said. And at the moment, I'm also fortunate enough to witness the first stage in rice production:

Yes, I realize these fantastically delicious baguette sandwiches are Vietnamese/French in origin, but they're virtually nonexistent in Thailand and are one of the things I look forward to eating when in Laos. More Things I Like About Laos to follow...

Yes, I realize these fantastically delicious baguette sandwiches are Vietnamese/French in origin, but they're virtually nonexistent in Thailand and are one of the things I look forward to eating when in Laos. More Things I Like About Laos to follow... And no, it's no isaan (northeastern Thailand). A pretty easy challenge for most of you, I imagine...

Sorry blogs have been slow in coming, but I'm on the road at the moment and have little time to spend at the computer. When I'm a bit more stationary, I'll be blogging on some of the interesting stuff I've seen and eaten in this country. In the meantime, be sure to check out the feature I've done on

And no, it's no isaan (northeastern Thailand). A pretty easy challenge for most of you, I imagine...

Sorry blogs have been slow in coming, but I'm on the road at the moment and have little time to spend at the computer. When I'm a bit more stationary, I'll be blogging on some of the interesting stuff I've seen and eaten in this country. In the meantime, be sure to check out the feature I've done on  Nang Loeng Market, located just north of Banglamphu, off Th Nakhorn Sawan, is among the city's oldest continuously operating markets. The recipient of a recently-finished makeover culminating in a fresh coat of paint, new tiles and a rather garish sign, Nang Loeng Market is hardly looking its 100+ years. However, in all honesty, the label 'market' is a bit of misnomer here. The Nang Loeng of today resembles something more of a food court than a fresh market, and the main hall is dominated not by piles of greens or still-flapping fish, but rather by stalls selling prepared dishes:

Nang Loeng Market, located just north of Banglamphu, off Th Nakhorn Sawan, is among the city's oldest continuously operating markets. The recipient of a recently-finished makeover culminating in a fresh coat of paint, new tiles and a rather garish sign, Nang Loeng Market is hardly looking its 100+ years. However, in all honesty, the label 'market' is a bit of misnomer here. The Nang Loeng of today resembles something more of a food court than a fresh market, and the main hall is dominated not by piles of greens or still-flapping fish, but rather by stalls selling prepared dishes:

as seen in Bangkok's Chinatown. Any idea what this stall serves?

as seen in Bangkok's Chinatown. Any idea what this stall serves? Tim Hetherington's image of US soldier in Afghanistan is the 2007 World Press Photo Photo of the Year.

Tim Hetherington's image of US soldier in Afghanistan is the 2007 World Press Photo Photo of the Year.  As the painfully obvious name ('Phat Thai House') suggests, this is indeed a phat thai restaurant, but there are no noodles in today's post. Rather, walking by this tiny shophouse restaurant in Olde Bangkok, I was drawn to the vast array of ingredients used to make khao khluk kapi, rice cooked in shrimp paste and served with a vast array of toppings. This is one of my favourite Thai dishes, and as it seems to be little-known among visitors to Thailand, I've been working tirelessly to promote it, with previous mentions

As the painfully obvious name ('Phat Thai House') suggests, this is indeed a phat thai restaurant, but there are no noodles in today's post. Rather, walking by this tiny shophouse restaurant in Olde Bangkok, I was drawn to the vast array of ingredients used to make khao khluk kapi, rice cooked in shrimp paste and served with a vast array of toppings. This is one of my favourite Thai dishes, and as it seems to be little-known among visitors to Thailand, I've been working tirelessly to promote it, with previous mentions

Bangkok's Saphan Phut, Memorial Bridge, at night. A composite of five separate images stitched together with Photoshop CS3's Photomerge function. For larger image, go

Bangkok's Saphan Phut, Memorial Bridge, at night. A composite of five separate images stitched together with Photoshop CS3's Photomerge function. For larger image, go  Apparent apathy at Bangkok's central train station.

Apparent apathy at Bangkok's central train station. In reading Suthon Sukphisit's excellent Cornucopia column, which runs every Saturday in the

In reading Suthon Sukphisit's excellent Cornucopia column, which runs every Saturday in the

Nong New, a stall in Bangkok's Chinatown, specialises in a few dishes that you're more than likely to run into in this part of town: birds' nest and shark fin soup. I've had bird nest soup a couple times, and find it too sweet for my taste. And shark fin soup is a ridiculous dish that's more superstition than cuisine. But there's still reason to visit Nong New's stall; he's known for making some of the best phat mee hong kong, 'Hong Kong-style fried noodles', in the area:

Nong New, a stall in Bangkok's Chinatown, specialises in a few dishes that you're more than likely to run into in this part of town: birds' nest and shark fin soup. I've had bird nest soup a couple times, and find it too sweet for my taste. And shark fin soup is a ridiculous dish that's more superstition than cuisine. But there's still reason to visit Nong New's stall; he's known for making some of the best phat mee hong kong, 'Hong Kong-style fried noodles', in the area:

Ladyboy prostitute, Bangkok's Chinatown

Ladyboy prostitute, Bangkok's Chinatown

Mukdahan is probably the least known and quietest of Thailand's large cities located along the Mekong. Despite this, it had one of the region's best night markets:

Mukdahan is probably the least known and quietest of Thailand's large cities located along the Mekong. Despite this, it had one of the region's best night markets:

Khai katha, literally 'pan eggs', is a dish I came across in virtually every Thai town that bordered the Mekong River. It's apparently a Vietnamese take on fried eggs for breakfast, although I don't recall having seen it there. The eggs, fried up in a tiny aluminum pan (the katha), are supplemented with thin slices of kun chiang (Chinese sausage), muu yor (Vietnamese sausage), sliced green onions, and unusually for Thailand, ground black pepper. The dish is also accompanied by bread, which at the better places, takes the form of a freshly-toasted French-style baguette (although it must be said that the Thai ones are nowhere near as good as their Vietnamese and Cambodian counterparts).

Khai katha, literally 'pan eggs', is a dish I came across in virtually every Thai town that bordered the Mekong River. It's apparently a Vietnamese take on fried eggs for breakfast, although I don't recall having seen it there. The eggs, fried up in a tiny aluminum pan (the katha), are supplemented with thin slices of kun chiang (Chinese sausage), muu yor (Vietnamese sausage), sliced green onions, and unusually for Thailand, ground black pepper. The dish is also accompanied by bread, which at the better places, takes the form of a freshly-toasted French-style baguette (although it must be said that the Thai ones are nowhere near as good as their Vietnamese and Cambodian counterparts).

Golden Mount, Bangkok

Golden Mount, Bangkok

From Chiang Mai, I decided to go back home the long way: over to Chiang Rai, then back to Bangkok along Thailand's length of the Mekong River. The vast majority of this trip took place in isaan, Thailand's rural northeast, which food-wise, normally inspires thoughts of sticky rice, som tam and grilled chicken. However the residents of the Mekong region love their Vietnamese food. I had heard this before, but was not prepared for just how completely ubiquitous and utterly delicious Vietnamese food was. In Nakhorn Phnom, for example, there were three Vietnamese restaurants within walking distance of each other, but not a sticky rice steamer or mortar and pestle to be seen. I'm going to profile some of these dishes and restaurants in the next couple blogs, beginning with this amazing restaurant in Nong Khai.

From Chiang Mai, I decided to go back home the long way: over to Chiang Rai, then back to Bangkok along Thailand's length of the Mekong River. The vast majority of this trip took place in isaan, Thailand's rural northeast, which food-wise, normally inspires thoughts of sticky rice, som tam and grilled chicken. However the residents of the Mekong region love their Vietnamese food. I had heard this before, but was not prepared for just how completely ubiquitous and utterly delicious Vietnamese food was. In Nakhorn Phnom, for example, there were three Vietnamese restaurants within walking distance of each other, but not a sticky rice steamer or mortar and pestle to be seen. I'm going to profile some of these dishes and restaurants in the next couple blogs, beginning with this amazing restaurant in Nong Khai.

Reflections on Th Yaowarat, the main street in Bangkok's Chinatown

Reflections on Th Yaowarat, the main street in Bangkok's Chinatown

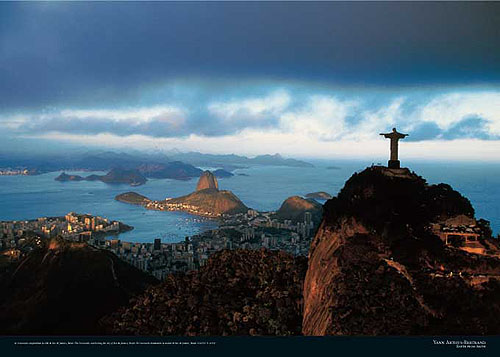

The Corcovado overlooking the city of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Image courtesy of Yann Arthus-Bertrand.

The Corcovado overlooking the city of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Image courtesy of Yann Arthus-Bertrand.