I’m in very good culinary company here in Mae Hong Son. As soon the owner of the house I’m renting learned that I have an interest in the local food, she started bringing me local sweets and snacks on a daily basis. This morning she went out of her way to bring me a local dish of sticky rice steamed with coconut milk and turmeric and served with local-style meatballs (more on this later), something that I had mentioned the previous day. My next-door neighbour, Phii Laa, is equally generous, and possibly even more enthusiastic. Once she learned that I was interested in the local eats she’s been in my kitchen every morning since, sharing a new recipe.

I’m in very good culinary company here in Mae Hong Son. As soon the owner of the house I’m renting learned that I have an interest in the local food, she started bringing me local sweets and snacks on a daily basis. This morning she went out of her way to bring me a local dish of sticky rice steamed with coconut milk and turmeric and served with local-style meatballs (more on this later), something that I had mentioned the previous day. My next-door neighbour, Phii Laa, is equally generous, and possibly even more enthusiastic. Once she learned that I was interested in the local eats she’s been in my kitchen every morning since, sharing a new recipe.

The first recipe Phii Laa shared is one I only came across recently. Khao som literally means ‘sour rice’, and is local a dish of balls of rice made sour by the addition of tomato and tamarind. The dish is traditionally served with yam thua, ‘bean salad’, the recipe for which can also be adapted to make any sort of local salad where the main ingredient, which here can range from tender fern shoots (a popular local ingredient) to sour leaves, is first par-boiled. In my next blog I’ll demonstrate how to make a saa, another type of local salad centred around fresh (as opposed to par-boiled) greens or veggies.

The ingredients required for khao som and yam thua are pretty basic and I imagine all are generally available even in the west, except for nam phrik phong:

a mixture of thua nao (disks of dried soybean), dried chili, salt and MSG, all ground to a fine powder. If you’re determined, I’d suggest just substituting a pinch of finely ground dried chili flakes and some salt, although the dish will be missing a truly local flavour in thua nao.

And if you haven’t done it before, making crispy deep-fried garlic and garlic oil is a snap:

Simply get your hands the smallest cloves of garlic you can find, chop them up coarsely (skin and all), and simmer in a generous amount of oil over medium heat until the garlic is just beginning to become crispy. When this happens remove mixture to a heatproof container and allow to cool.

And as always, ingredient measurements below are estimated; Phii Laa, like most Thai cooks, doesn’t use measuring utensils, instead cooking by taste and feel.

Khao som & yam thua (Sour Shan-style rice and bean salad)

Uncooked rice, 2 cups

Strained tamarind pulp, 1 cup

Chopped tomatoes, 2 cups

Salt, 1 tsp

Turmeric powder, ½ tsp

Sugar, 1 Tbsp

French beans

Shrimp paste, 1 Tbsp

Nam phrik phong, 2 Tbsps

Ground roasted white sesame seeds, 4 Tbsp

Shallots, sliced, 4

Garlic oil & crispy deep-fried garlic

Deep-fried dried chilies

Cook rice with at least three cups of water (the rice is supposed to have a soft consistency). When cooked, allow to cool slightly.

Combine tamarind pulp, tomatoes, salt, turmeric and sugar in a wok over low heat. Simmer, stirring occasionally, until reduced to a thick paste:

about 10 minutes. Set aside.

Prepare beans by removing the strings and chopping:

Par-boil beans until just cooked, about a minute, and shock in cold water. Set aside.

In a wok over medium heat, dissolve shrimp paste in ¼ cup of water. When shrimp paste is fully incorporated, add nam phrik phong and sesame. Combine thoroughly and turn off heat. Allow to cool slightly, add sliced shallots and beans and mix thoroughly. Remove to a serving dish and top with crispy fried garlic and garlic oil.

When rice is cool enough to handle, combine ¾ of the tamarind mixture with cooked rice.

Taste and season with remaining tamarind mixture and/or salt if necessary.

Coating hands in a bit of the garlic oil, shape rice mixture into golf ball-sized balls:

Arrange on a plate and drizzle with plenty of crispy garlic, oil and deep-fried chilies.

Serve dish, as illustrated at the top of this post, on individual plates with a generous serving of the bean salad.

or met ya ruang, or kayii or kayuu. Or met thai khrok or met hua khrok. Or perhaps even met mamuang himaphaan. These are all the different Thai dialect words for cashew nuts. The English word, cashew, is almost certainly a cognate of the Portuguese cajou, which apparently originates from the Tupi word acajú, and which is most likely also the source of kayuu, the term used on Phuket, the thought being that the Portuguese first introduced the fruit to Asia from its native Brazil.

or met ya ruang, or kayii or kayuu. Or met thai khrok or met hua khrok. Or perhaps even met mamuang himaphaan. These are all the different Thai dialect words for cashew nuts. The English word, cashew, is almost certainly a cognate of the Portuguese cajou, which apparently originates from the Tupi word acajú, and which is most likely also the source of kayuu, the term used on Phuket, the thought being that the Portuguese first introduced the fruit to Asia from its native Brazil.

Undoubtedly my favourite dish I encountered in Bangladesh was phuchka (known elsewhere as

Undoubtedly my favourite dish I encountered in Bangladesh was phuchka (known elsewhere as

In general, food in Bangladesh wasn't much to write home about. There were a few interesting dishes, some of which I'll blog about soon, but most of our meals seemed to be endless but eerily similar variations on mutton and rice. The one area we were most impressed with was sweets. These ranged from syrupy-sweet golab jam, below:

In general, food in Bangladesh wasn't much to write home about. There were a few interesting dishes, some of which I'll blog about soon, but most of our meals seemed to be endless but eerily similar variations on mutton and rice. The one area we were most impressed with was sweets. These ranged from syrupy-sweet golab jam, below:

I've spent the last several days traveling and taking photos in Bangladesh. It's dirty, noisy, crowded and the food isn't much to speak of. But the people here are by leaps and bounds the friendliest, kindest folks I've ever come across anywhere, and in a bizarre way, despite the garbage, pollution and poverty, Bangladesh is probably the most photogenic place I've ever been. Will be posting some more images here, including a bit of food-related stuff on

I've spent the last several days traveling and taking photos in Bangladesh. It's dirty, noisy, crowded and the food isn't much to speak of. But the people here are by leaps and bounds the friendliest, kindest folks I've ever come across anywhere, and in a bizarre way, despite the garbage, pollution and poverty, Bangladesh is probably the most photogenic place I've ever been. Will be posting some more images here, including a bit of food-related stuff on  get out of the hot spring. Or to put it in my context, leave Mae Hong Son. This was done with a great deal of reluctance, but it was beginning to get intolerably hot and smoky, a profound change from the first two weeks of my stay when I had to wear a fleece jumper and thick socks until lunch. One sign of the impending hot season is the floating restaurants that go up on the Mae Nam Pai:

get out of the hot spring. Or to put it in my context, leave Mae Hong Son. This was done with a great deal of reluctance, but it was beginning to get intolerably hot and smoky, a profound change from the first two weeks of my stay when I had to wear a fleece jumper and thick socks until lunch. One sign of the impending hot season is the floating restaurants that go up on the Mae Nam Pai: And now I'm back home in hot, sweltering Bangkok, although yet again in transition: tomorrow I'm off to Bangladesh (!) for a week and after that, will be in Phuket for a few days. An almost perverse contrast in destinations, for sure. Depending on the Internet situation in Bangladesh, I'll try to do some blogging, but can't make any promises.And lastly, I've entered a contest/marketing ploy for a prize to embark on my photographic 'Dream Assignment'. My dream assignment? Collaborating with a

And now I'm back home in hot, sweltering Bangkok, although yet again in transition: tomorrow I'm off to Bangladesh (!) for a week and after that, will be in Phuket for a few days. An almost perverse contrast in destinations, for sure. Depending on the Internet situation in Bangladesh, I'll try to do some blogging, but can't make any promises.And lastly, I've entered a contest/marketing ploy for a prize to embark on my photographic 'Dream Assignment'. My dream assignment? Collaborating with a  I was hoping to blog about a community group in Pha Bong, 10km outside Mae Hong Son, that gets together every weekend to make a spice mixture for laap, but when I drove out there on Saturday they weren't able to get enough lemongrass (they need a lot of lemongrass) and had rescheduled for the next day. Unfortunately I was leaving Mae Hong Son then and did not get a chance to witness this...

I was hoping to blog about a community group in Pha Bong, 10km outside Mae Hong Son, that gets together every weekend to make a spice mixture for laap, but when I drove out there on Saturday they weren't able to get enough lemongrass (they need a lot of lemongrass) and had rescheduled for the next day. Unfortunately I was leaving Mae Hong Son then and did not get a chance to witness this...

Fans of Thai food in the west are likely familiar with laap (or larb or laab), a minced meat ‘salad’ tart with lime juice and fragrant from the addition of khao khua, roasted and ground sticky rice. Fewer are likely familiar with the northern version of the dish of the same name, which contains neither khao khua nor lime juice, and instead gains its unique flavour from a mixture of dried spices specific to northern Thailand.

Fans of Thai food in the west are likely familiar with laap (or larb or laab), a minced meat ‘salad’ tart with lime juice and fragrant from the addition of khao khua, roasted and ground sticky rice. Fewer are likely familiar with the northern version of the dish of the same name, which contains neither khao khua nor lime juice, and instead gains its unique flavour from a mixture of dried spices specific to northern Thailand.

Paa Add cooks and sells a variety northern Thai and Shan dishes at Kaat Yaaw, Mae Hong Son’s evening market. She can be a bit of a hard sell, but is an extremely talented cook, her dishes both well executed and perfectly seasoned (her local-style fern shoot salad is a culinary masterpiece), even if you’re not familiar with the cuisine. I’d been buying her delicious curries, stir-fries and salads since coming here, when one day I asked her if she’d mind if I stopped by to see how they were made. She immediately dropped what she was doing and stared at me for at least five seconds. ‘Are you going to open a restaurant abroad?’ she asked.

Paa Add cooks and sells a variety northern Thai and Shan dishes at Kaat Yaaw, Mae Hong Son’s evening market. She can be a bit of a hard sell, but is an extremely talented cook, her dishes both well executed and perfectly seasoned (her local-style fern shoot salad is a culinary masterpiece), even if you’re not familiar with the cuisine. I’d been buying her delicious curries, stir-fries and salads since coming here, when one day I asked her if she’d mind if I stopped by to see how they were made. She immediately dropped what she was doing and stared at me for at least five seconds. ‘Are you going to open a restaurant abroad?’ she asked.

This morning I took a drive along Hwy 1285, an isolated road that twists 15km between mountain valleys to the village of Huay Phueng, not far from the Burmese border. It's getting warmer in Mae Hong Son, but driving a motorcycle at 7am, in the shadows of the hills, it was so cold I quickly lost the feeling in my hands.

This morning I took a drive along Hwy 1285, an isolated road that twists 15km between mountain valleys to the village of Huay Phueng, not far from the Burmese border. It's getting warmer in Mae Hong Son, but driving a motorcycle at 7am, in the shadows of the hills, it was so cold I quickly lost the feeling in my hands.

Jin lung are a local type of meatball, rich in fresh herbs and often yellow in colour from the addition of dried turmeric powder. They're most commonly made from pork, but beef and fish versions can be found on occasion. In Mae Hong Son's morning market they're sold in Indian-style pots in a generous amount of the yellow cooking oil, and when ordered, two or four (the serving sizes here are really small) are bagged up with a drizzle of the oil and some deep-fried crispy garlic.

Jin lung are a local type of meatball, rich in fresh herbs and often yellow in colour from the addition of dried turmeric powder. They're most commonly made from pork, but beef and fish versions can be found on occasion. In Mae Hong Son's morning market they're sold in Indian-style pots in a generous amount of the yellow cooking oil, and when ordered, two or four (the serving sizes here are really small) are bagged up with a drizzle of the oil and some deep-fried crispy garlic.

The bloggers at EatingAsia recently pointed out that

The bloggers at EatingAsia recently pointed out that

but I think I might have to draw the line at Mr Cooker brand tinned beef curry from Myanmar.

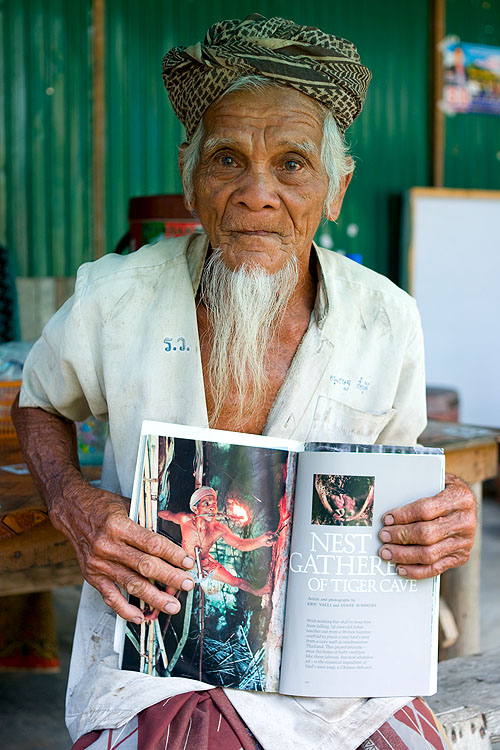

but I think I might have to draw the line at Mr Cooker brand tinned beef curry from Myanmar. A vendor of Burmese goods at the town's morning market

A vendor of Burmese goods at the town's morning market  Khun Yay (‘Grandma’), my landlord’s mother, is originally from Ayuthaya, but moved to Mae Hong Son when she was 14 – more than 70 years ago. 'It took us three months to walk here from Ayuthaya,' she explained to me, adding that part of the journey was done on elephant back. After seven decades here she’s essentially a native of the city, and even used to earn extra money by selling Thai Yai/Shan sweets. She can also make the local savoury dishes, and everybody in the family agrees that she makes a mean hang lay.

Khun Yay (‘Grandma’), my landlord’s mother, is originally from Ayuthaya, but moved to Mae Hong Son when she was 14 – more than 70 years ago. 'It took us three months to walk here from Ayuthaya,' she explained to me, adding that part of the journey was done on elephant back. After seven decades here she’s essentially a native of the city, and even used to earn extra money by selling Thai Yai/Shan sweets. She can also make the local savoury dishes, and everybody in the family agrees that she makes a mean hang lay.

Yesterday, Phii Laa, my neighbour, came over with the tray of ingredients pictured above and a desire to share her recipe for saa, a local type of yam or Thai-style ‘salad’. I was excited about this because in Mae Hong Son there are several variations on the standard Thai yam that I've yet to get my head around: there’s the type I mentioned in the

Yesterday, Phii Laa, my neighbour, came over with the tray of ingredients pictured above and a desire to share her recipe for saa, a local type of yam or Thai-style ‘salad’. I was excited about this because in Mae Hong Son there are several variations on the standard Thai yam that I've yet to get my head around: there’s the type I mentioned in the

I’m in very good culinary company here in Mae Hong Son. As soon the owner of the house I’m renting learned that I have an interest in the local food, she started bringing me local sweets and snacks on a daily basis. This morning she went out of her way to bring me a local dish of sticky rice steamed with coconut milk and turmeric and served with local-style meatballs (more on this later), something that I had mentioned the previous day. My next-door neighbour, Phii Laa, is equally generous, and possibly even more enthusiastic. Once she learned that I was interested in the local eats she’s been in my kitchen every morning since, sharing a new recipe.

I’m in very good culinary company here in Mae Hong Son. As soon the owner of the house I’m renting learned that I have an interest in the local food, she started bringing me local sweets and snacks on a daily basis. This morning she went out of her way to bring me a local dish of sticky rice steamed with coconut milk and turmeric and served with local-style meatballs (more on this later), something that I had mentioned the previous day. My next-door neighbour, Phii Laa, is equally generous, and possibly even more enthusiastic. Once she learned that I was interested in the local eats she’s been in my kitchen every morning since, sharing a new recipe.

Khao ya koo is the Shan/Thai Yai name for a type of sweetened sticky rice. Other than simply being a sweet snack, the dish has strong associations with celebration, as it's only made on certain holidays. It also has ties with community, and as you'll see, is one distinctly local method of making merit (kwaa loo in the local dialect).

Khao ya koo is the Shan/Thai Yai name for a type of sweetened sticky rice. Other than simply being a sweet snack, the dish has strong associations with celebration, as it's only made on certain holidays. It also has ties with community, and as you'll see, is one distinctly local method of making merit (kwaa loo in the local dialect).

This is a Thai Yai/Shan dish that one sees for sale all over Mae Hong Son, and it combines ingredients essential to virtually every local dish: soybeans (both in the form of tofu and thua nao, disks of dried soybeans), garlic, tomatoes and turmeric. However, just like any other dish, there appears to be several different ways to make thua phoo khua. My neighbour claims that thua nao has no place in the chili paste of this dish, and that she normally uses fresh chilies. The ladies selling meat in the morning market told me that I have to use thua nao and dried chilies... I've followed the latter method, combined with a recipe from a Thai-language cookbook printed in Mae Hong Son.

This is a Thai Yai/Shan dish that one sees for sale all over Mae Hong Son, and it combines ingredients essential to virtually every local dish: soybeans (both in the form of tofu and thua nao, disks of dried soybeans), garlic, tomatoes and turmeric. However, just like any other dish, there appears to be several different ways to make thua phoo khua. My neighbour claims that thua nao has no place in the chili paste of this dish, and that she normally uses fresh chilies. The ladies selling meat in the morning market told me that I have to use thua nao and dried chilies... I've followed the latter method, combined with a recipe from a Thai-language cookbook printed in Mae Hong Son.